By TOM ODHIAMBO

Nuruddin Farah is one of East Africa’s most prolific writers. He has written novels, short stories, plays and essays. His work has been translated into several languages.

Nuruddin’s first novel, From a Crooked Rib has been in print for slightly more than half a century. It was first published in 1970 by James Currey. This novel counts among the first African stories that dealt with the question of women in the society.

A Crooked Rib should be read alongside Mariama Ba’s So Long a Letter and Nawal el Saadawi’s Woman at Point Zero as Africa’s ‘feminist’ narratives.

FEMALE PROTAGONIST

The story of Ebla, the female protagonist of the novel, is a tragic one. It is the tale of a woman trapped in a society that always tilts the scales against her. She runs away from an ‘arranged’ marriage to an older man, ends up sexually abused in the city where she thought she would gain freedom from control by men, and is perpetually struggling to retain some dignity in her life.

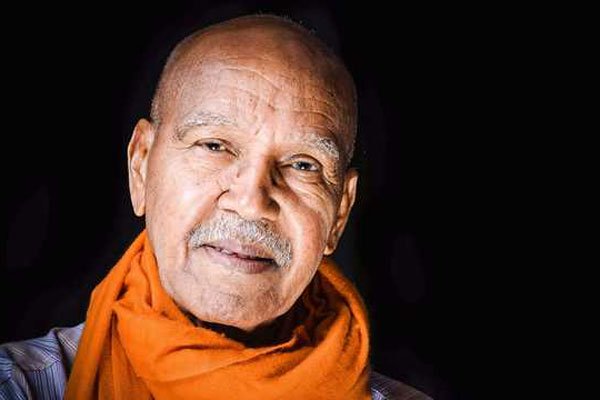

Nuruddin was in Nairobi recently to celebrate the 50th anniversary of From a Crooked Rib at Cheche Bookshop, Lavington. In a conversation with Tom Odhiambo, he reflected on a number of issues relating to why he wrote the story, what the novel has become since it was published and the subject of African women in the past and today.

On the origins of From a Crooked Rib

“… From a Crooked Rib is not my first novel. There were two novel manuscripts before From a Crooked Rib. I have no idea where the manuscripts are. I had sent the manuscript of the first novel called To Make a Deal to a publishing house in New York.

They looked at it and asked me to revise it and I lost interest. There was another novel and again I lost interest in it. But the one novel that kept me grounded was From A Crooked Rib. Now, From a Crooked Rib has become, in a way, mythical because when I sent it to the publishing house, the editor, James Currey, wrote a letter to me. In those days there were no emails. So, he wrote a letter to me and he said, ‘We would like to ask you one simple question, are you a man or a woman?’

How was the novel received when it was published?

No one, in fact, bothered to review From a Crooked Rib when it came out. It was never reviewed until after I published many other novels.

But it has many stories to it. One of the reasons why it has many stories is because it travelled by word of mouth.

People told each other, ‘this is a book that you must read.’ With no reviews and no name recognition and the fact that I was living in Mogadishu at the time, with the language of instruction in schools being Italian, all these things downplayed the importance of the novel and the subject matter.

One other fascinating story is that besides my publishing editor writing to me and asking if I was a man or woman, till this day I receive letters addressed to ‘Mrs Farah.’

What do you think about the protagonist in From a Crooked Rib. If Ebla was alive today, she would be in her 70s. Would her situation be better, still in a context (Somalia) in which the book was written?

I doubt it very much that her situation would be better today. And the reason is because the situation of women in much of Africa and much of the world has changed very little. It continues to be a struggle for one to be a woman and to have a life comparable to that of the boy.

However, I wrote the new prologue of this novel two months ago.

Why a new prologue?

We are making a film based on From a Crooked Rib. And because of the way films work, I have decided to give a different prologue so that you will have Ebla who is now in her early 70s and who now lives in Toronto.

She is telling the story of her life to her granddaughter whose mother wants to bring her back to Somalia to have her infibulated. She fights very hard to make sure that that daughter is not circumcised.

Is there a literary project focusing on a search for humanism in your writing?

Well, I did not start off thinking that I would be able to do it (write From a Crooked Rib). Remember, I was 22 years old, a second year student in a university in India, and obviously dealing with problems that a young 22-year old person has to deal with.

In my second year, I had already written two novels by the time that I came to From a Crooked Rib. How do I go about searching for freedom when I come from a country that has suffered colonialism and conquest? So, I was not looking at myself as a person.

I was looking at myself as a member of humanity, negotiating all the difficulties that one is supposed to come across. And at that time, fortunately for me, I came across a play by a Norwegian playwright, called Henrik Ibsen, A Doll’s House.

What fascinated me that time at the age of 22 was to see that the principle character of the play, towards the end of the play, leaves her husband, closes the door and says, ‘To hell with you and with everything else that you would have presented’.

This woman lives in a middle-class family, but not quite happily, and if she could leave whatever comforts that she had, I thought Ebla at the age of 18, whose hand has been given in marriage to a man who is 62, should have no life.

And, therefore, she thought, it is time for me to go, and go in search of my own humanity. And the reason is because I have no life to live here.

How has your transnational identity impacted your writing?

Well, if I stand up now, and I stand on a piece of ground, that on which I am standing becomes invisible to me.

Being distant from Somalia, living in India, which I went to when I was 19, enabled me to take a very concentrated look into Somalia.

It enabled me to seek a Somalia that I would not have seen had I continued to live there. Therefore, distance distils, distance makes you see better.

Source: Daily Nation