Dr. Aweys Omar Mohamoud

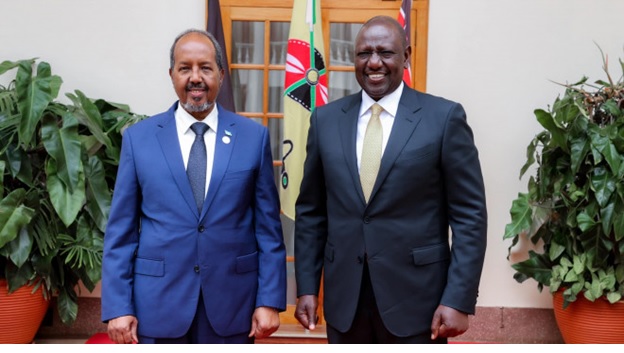

Parts I and II of this series covered the views of President William Ruto of Kenya on family nepotism contrasted with those of President Hassan Sheikh Mohamoud of Somalia. This piece covers perceptions of cronyism in President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s government; and Part IV (to come next) shall cover perceptions of corruption and the role of authentic leadership in achieving anti-corruption success.

“I’ll sponsor one hundred PhDs,” President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud faithfully promised to graduating students and assembled guests in a graduation address at a facility in the heavily fortified Halane camp in Mogadishu, in December last year. But this was no ordinary graduation exercise. In fact, it was the President’s own doctoral graduation ceremony. Apparently, the President was writing a doctoral thesis in the years he was campaigning for reelection after he lost power to former President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo in Feb. 2017.

In his address, the President (a professor by profession) cheerfully expounded a favourite topic: the role of education, and higher education in particular, in creating a well-trained workforce with technical and managerial skills and in bringing about the attitudinal changes necessary for socialization, modernization and the overall transformation of society from war-mongering to peaceful co-existence.

One wonders if the President was expressing these views out of personal moral convictions or was simply showing off his great learning on the subject. His detractors would say he was doing the latter. What’s the point of ‘sponsoring hundred new PhDs,’ they’d say, if the President has no time for the multitudes of highly qualified Somali professionals inside and outside the country and, instead, surrounding himself with yes-men and opportunists lacking capability or qualifications, in exchange for ongoing blind loyalty.

In Somali society, leaders place extraordinary importance on loyalty from those they have rewarded. To expand their power base and to push forward their political agendas, they appoint loyal subordinates and expect unreserved devotion and unswerving loyalty from them. Those with weak moral principles or lack honesty are the ones more willing to provide such unreserved devotion and unswerving loyalty as the leaders demand. Even if the decisions being made by the leader are egregious, those weaklings they appoint who lack skill and can’t make an effort are the ones more willing to never challenge them. That’s the link between cronyism and gratitude, where cronyism is the act of dispensing favors to individuals regardless of their abilities.

When a leader makes it a practice to hire and promote people who generally lack the skill, experience or qualifications for a job with the expectation of blind loyalty, they engage in cronyism. Cronyism is defined as the “appointment of friends and associates to positions of authority, without proper regard to their qualifications.” It is the opposite of meritocracy, where appointments are made based on qualifications. Cronyism can lead to unfair advantages for individuals who may not be the most qualified or capable, and can undermine principles of fair selection processes based of individual ability or achievement.

While previous governments have also been accused of favouring family and friends, President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s government is said to have been particularly infected with a culture of cronyism in appointing friends, family members, and political donors and allies, who lack merit or achievement, to public positions. These cronies and allies of the President are also said to be favoured with influence and special access to public resources.

It may not be illegal for the President to appoint an ally or a family relative to a government position, but it is still a conflict of interest because by doing so, he’s not objectively determining who’s best qualified for that position. Again, while the President or other public officials awarding government contracts to relatives or friends may not be illegal, it is still a direct conflict of interest. In other words, when a government official’s economic interest rather than the public interest is served, even if it’s not an outright crime, it represents an abuse of public trust in government and an evasion of accountability and transparency.

The FGS, under President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s 2nd term, is said to have become an entity where who you know apparently means more than what you know, and where credentials, qualifications and work experience conferred no real advantage. A grossly incompetent opportunist trading on favours and family connections stands a better chance of success than a highly meritorious individual. The cronyism works for the most part subtly and invisibly (of course, the nepotism is in the open, especially now that the President had encouraged officials to never give ground [yaan laga jixinjixin] to those who clamour for merit-based appointments), creating opportunities for those who have connections, and increasingly excluding those who don’t. This of course violates Somali people’s basic sense of fairness and elicits strong reactions of revulsion and distaste, especially when the crony (the beneficiary) is manifestly unqualified.

I have written the above paragraph before I heard the appointment of Gen Ibrahim Sheikh Muhyadin Aw-Addow on 19 June 2023 as the new Commander of the Somali National Army (SNA). I and many others can attest to the fact that, unlike his predecessor, the new SNA Commander trained at the Jaalle Siyaad Military Academy in Mogadishu and was commissioned officer of the Somali National Army in the mid-1980s. Granted he’s got connections, but the new army chief is also someone with professional military training, credentials and experience and, therefore, the service he’d be rendering to the public would hopefully not be an inferior one. The claims made on social media that he was more of a ruling party apparatchik than a military commander and seriously corrupt when he was commanding the Presidential Guard in President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s first term cannot be corroborated in this piece.

The consequences of cronyism are vast and deep: it corrupts government, reduces trust in societal institutions, promotes amoral selfishness, throttles meritocracy, reinforces incompetence and inefficiency from unfair competition, and violates people’s right to fair, impartial, and equitable treatment. In addition, cronyism adversely affects the performance of state institutions, saps the morale of those who themselves have not benefited from it, serves to strengthen the grip of a few at the top, and imposes a constraint on the government’s ability to learn and adapt to changes.

Both cronyism and its’ close cousin, nepotism, are problematic in a society based on equality and merit. The problem is that present-day Somalia is not based on equality and merit. It is based on a power-sharing arrangement known as 4.5 and, with it, comes pressure and expectations on government leaders to commit acts of cronyism by appointing individuals to positions of authority, without proper regard for their qualifications. So we are told!

But are leaders truly obliged by so-called 4.5 arrangements to appoint cronies to positions of power? Or is this something that they themselves want to do as a means of developing a personal power base? Because cronyism involves showing favour to some at the expense of others, in fact most Somali people would perceive it as not only corrupt and unethical but a moral perversion at the core of the perpetual crisis in ordinary people’s confidence in their government. However, perceiving something and acting on it or doing something about it are completely different things.

Cronyism has become a fact of life because government leaders and public officials are keen on cultivating loyal, obedient, and submissive subordinates as a means of developing a personal power base to their own advantage. Such acts of consolidating power are considered normal, and won’t be scorned by society. Using public office to benefit oneself and one’s family and friends is a shared belief that is expected, tolerated, and widespread. In essence, corruption has become a social norm because people believe that the purpose of obtaining office is to provide one’s family and friends with money, goods, favours, or appointments. That has been the default social norm, in Somalia as elsewhere, throughout much of history. Only gradually has the principle of equal treatment for all before the law emerged, and in most countries it is still a work in progress.

The issue, of course, isn’t how individuals can behave better but how institutions can behave better. Can the FGS, under President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s 2nd term, come up with (or enforce, if they exist) transparent and objective performance appraisal systems to ensure that rewards are allocated based on merit rather than loyalty? And, when it comes to recruitment and selection, can it ensure that candidates with the best qualifications, not the best connections, are hired?

Leaders make a major difference when it comes to fighting corruption because they can provide an ethical or less-than-ethical pattern of conduct for their officials, civil servants, security forces, and citizens at large to follow. President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has recently been making public statements, especially in mosques, promising to deploy all legal instruments and measures to prevent and fight corruption and a few officials who were publicly accused of wrong-doing is said to have either been ‘arrested’ or gone underground, issuing denials through social media.

It is to this story and the overall public perception of corruption under the President HSM’s FGS that we turn to next in Part IV.

Dr. Aweys Omar Mohamoud

Email: aweys6@aol.com

__________

Related articles:

Leave a Reply