By Stephany Jay

Ethiopia’s prime minister is making headlines as a Trudeau-like liberal reformer. But behind his progressive sheen, his economic policies are set to accelerate inequality and poverty.

What happens in Davos, stays in Davos — at least for the majority of the Ethiopian public, who takes little interest in the exclusive annual gathering of the global financial elite. This year, however, the speech by Ethiopia’s new prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, at the 2019 World Economic Forum was shared widely on social media. Its spread highlighted the pop-star-like status that the country’s new, charismatic leader enjoys among Ethiopians, especially the country’s youth.

The forty-four-year-old prime minister addressed the World Economic Forum’s jet-setting global rich in their own language: literally, in English, but also in their neoliberal language of removing red tape for business, the power of the private sector, open markets, and integration (including Ethiopia’s commitment to joining the World Trade Organization).

Ahmed’s speech epitomized the usual pitch for global capital to come to cash-strapped developing countries (high returns! tax holidays!). But it also provided important insights on where the country may be headed, following its change of leadership in 2018 after years of protests.

The liberal establishment’s story of last year’s change in Ethiopia is a familiar one, told and retold countless times across the globe since the end of the Cold War. In 2018, this story goes, after decades of authoritarianism and a closed state-led economy, a new, enlightened leader finally arose to usher in a period of liberalization and the free market. Soon after, the World Bank approved US$ 1.2 billion in grants and loans in return for the standard package “towards supporting reforms in the financial sector including improving the investment climate.”

The new government already embarked on a partial privatization of key state-owned enterprises, as well as a hasty overhaul of the country’s regulatory framework in the hope of securing foreign capital for development. US trade delegations are ready to pounce on the lucrative state-owned Ethiopian Airlines, which will sell 45 percent of its stake to foreign investors.

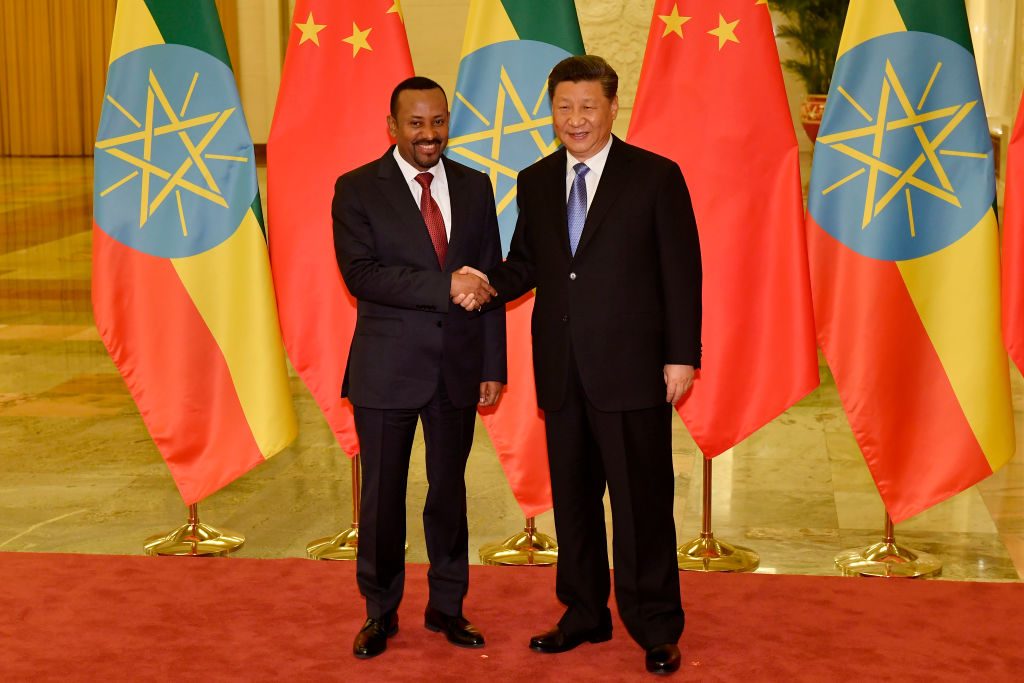

Recently, the German development minister complained that Germany could not just sit back and watch the US and China making billion-dollar investments in Africa: Germany should be involved too. Earlier this year, the German president and key German industrialists visited Addis to sign a memorandum of understanding between the Volkswagen Group and the Ethiopian Investment Commission to set up an automotive industry in Ethiopia. Nine months into Abiy’s new leadership, the new scramble for Ethiopia has already taken off.

Neoliberalism Versus the Developmental State

In order to make sense of the transformation underway in one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies, it’s important to understand Abiy’s political project, its social base, and how it operates within the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).

It’s ironic that the new prime minister’s 2019 World Economic Forum address was received with so much approval from global financial elites. Only seven years ago, Ethiopia’s former prime minister Meles Zenawi hosted the 2012 World Economic Forum on Africa in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa. There, he shocked the international financial elite by telling them that neoliberalism was a failed project.

Meles, who ruled as prime minister from 1995 until his death in August 2012, advocated instead his version of the “developmental state.” In this scheme, the state is in the driver’s seat of development, with ownership over key sectors and a tightly regulated private sector that serves to advance the overall national development agenda.

This model, which became official state doctrine in the early 2000s, is an eclectic mix of social and economic policies, some inspired by the East Asian “tiger” states but also more recently China’s industrial park and special economic zone industrialization model. Ethiopia also implements its own version of import substitution, allowing a small bloc of domestic capital to hold a state-sanctioned monopoly over key imports and local manufacturing.

Meles saw an opportunity for African countries to pursue an alternative development path in the rise of China and the breakdown of the Washington Consensus. This was his response to three decades of IMF policy, which turned Africa into what Meles called a “continental ghetto.”

Meles’s alternative path was financed with investments from China, estimated at more than US $12 billion between 2000 and 2015 and channeled towards infrastructure development (however, many of the country’s megaprojects went nowhere thanks to corruption). For instance, in 2017, a $4 billion railway, built and funded by the Chinese, opened to link Addis Ababa to the Port of Doraleh in Djibouti (where China opened its first overseas military base in August 2017).

Meles’s model, following in a long line of twentieth-century projects built on distortions of Marx, envisioned the development state’s historic role as serving the peasantry, the state’s “class base.” In contrast to neoliberalism, where wealth becomes concentrated among private capitalists, the activist state would ensure that wealth is broad-based and invested in expanding the nation’s technological capacity.

The practical results of two decades of the developmental state have been mixed at best. While the class of domestic capitalists is fairly small, wealth has become increasingly concentrated among a small group of party cronies and those directly linked to the military-run parastatal corporations. Though land is officially publicly owned, nomenklatura figures and business people (domestic and foreign) linked to the party’s upper echelon became extremely wealthy through corrupt land deals and urban Ethiopia’s ubiquitous construction projects. This network has alienated other factions of capital, including among the large US-based diaspora, that were not linked to the political elite. These frustrated capitalists have become the base for the free market push, couched in the language of liberal democracy, in Ethiopia.

Meanwhile, Ethiopia remains one of the poorest countries in the world, with a per capita GDP of about $860 (less than $2.50 per day) and a population of about 100 million expected to double over the next thirty years.

Still, under the developmental-state model, poverty declined from 45.5 percent in 2000 to 23.5 percent in 2016. This despite a population growth from 65 million in 2000 to 100 million 2016. Ethiopia has one of the lowest Gini coefficients (which measures income inequality) in Africa, much lower than neighboring “free market” Kenya. Large-scale and pro-poor investments in social services ensured that primary education (with gender parity) reached 100 percent, health coverage 98 percent, access to potable water 65 percent, and life expectancy at 64.6 years (up from about 50 years in 2000).

However, with Abiy’s Ethiopia aiming to become the world’s next low-wage paradise, inequality could increase dramatically. Foreign direct investment, while highly regulated and limited to certain sectors (mainly infrastructure, construction, agriculture, and textile), has taken on a significant role over the past ten years, growing from US $265,000 in 2005 to nearly US $4 billion in 2018.

With no private sector minimum wage in Ethiopia, low wages are seen as Ethiopia’s “comparative advantage” in the global race to the bottom, with the Ethiopian Investment Commission reporting that “the average wage of workers in the leather factories is US $45 per month, while the minimum wage in Guangdong is about US $300.” The recent Worker Rights Consortium’s investigation also reveals that Ethiopian factories are paying wages far lower than in any other apparel-exporting countries, with an average of 18 cents per hour.

In response to the International Trade Unions Confederation (ITUC) denouncing exploitative wages in Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector, local business-friendly media were quick to warn that it’s too soon to ponder wages. “The one prime opportunity the nation can offer investors is low-cost labour,” they argue, “and taking that away will only have negative consequences. It will just drive investment elsewhere and exasperate unemployment in the country.”

In a particularly telling convergence between the aid-industrial complex and Western foreign policy agendas, these low-labor-cost industrial parks double as European migration-control tools. Donors have pledged to mobilize $500 million for two industrial parks, as long as Ethiopia reserves a third of the projected 100,000 jobs for refugees. The necessary proclamation permitting refugees to work in the formal labor market was passed in January 2019. This was advocated for by Western governments who would never dream of proposing a 30 percent refugee quota on job-creation schemes at home.

Read more : The New Scramble for Ethiopia

Source: Jacobin