By Aden Ismail

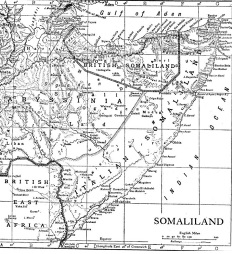

The Somali race, a nomadic tribe whose traditional warrior ethos led to centuries of ruthless conquest of the vast Horn of Africa region, have in the past six decades, been disoriented by the aftereffect of the European colonial legacies. In retrospect, their present-day territories – Somalia, Djibouti, Eastern Ethiopia and North Eastern Kenya – were much like a birthday cake, cut into pieces and divided among Britain, France, Italy and the Ethiopian Empire.

A Pan-Somali movement seeking to unite all the Somali people under one Greater Somalia came to the limelight in the early 20th century alongside the wave of African liberation struggles that convulsed in the continent. The new Somali Republic – composed of a union between British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland – subsequently adopted this Pan-Somali project as a central element in its geopolitical code leaving Mogadishu the custodial responsibility of advancing this dream. Relatedly, the five-pointed star emblazoned on the Somalia flag represents the five Somali territories ripped apart by the colonial powers.

However, unlike other African struggles, the Pan-Somali project had dim chances of success from the get-go. Chief among the obstacles, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, then seen as African elder statesmen with huge diplomatic heft, and resolutely pro-Western, vehemently opposed the Somali ambitions in the interest of their respective countries. Secondly, there was a broad-based consensus amongst African countries not to interfere with colonial boundaries lest this ignites widespread violence in the continent. A resolution adopted by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) heads of state in their 1964 Cairo summit further cemented this consensus albeit with strong reservations from Morocco and Somalia.

Nevertheless, a kick in the nuts to the Pan-Somali agitations was the ‘Ogaden region is an integral part of Ethiopia’ declaration by the OAU Good Offices meeting in Lagos, Nigeria, years later. Ogaden region is the Ethiopia-controlled region then claimed by Somalia and which has been a source of tension between the two countries causing the 1964 and 1977 wars. Unlike the Northern Frontier Districts (NFD) where Mogadishu seemed to have tacitly accepted the 1964 Cairo resolution – for it never sought military confrontation with Kenya – the Ogaden region question stands unique in its historical context.

Two adjacent African states occupying their territories created a ‘black enemies at the gates’ scenario in the minds of the Somali people. Compounding this was also the unsympathetic gesture of the OAU and its adoption of policies contrary to the Somali wishes. Unfortunately, two uncompromising African neighbours and the indifferent position of the larger black community to this cause harboured a deep sense of ethnic alienation among Somalis thereby severing the brotherhood bond that the newly liberated African masses much needed to embrace. Feeling betrayed, Somalis had to turn elsewhere for sympathy and support for their mission thus paving the way for a slow disengagement from the African identity. This identity redefinition was and still is, reflected in the views of the ordinary Somali.

Congenial allies found.

From 1950 to the 1970s when Somali nationalism was at its peak, tensions were also brewing in the Middle East between the Jewish and Arab people over Palestine. The ultra-nationalist ideology of Gamal Abdel Nasser found a receptive audience and swept through the streets of the Arab World. This also presented a great opportunity for the African-frustrated Somali nationalism cause. Centuries of trade links between them and Arabs, mythical genealogical Arab roots, geographical proximity, and a common religion, formed the perfect blend to invent a new Arab Identity or perhaps, forge a brothers-in-cause kind of comradeship between the two peoples. A strong pro-Arab orientation precipitated by Egypt’s membership – alongside Colombia and the Philippines – of the Trusteeship Advisory Council on the management of the Italian Somaliland had already entrenched itself among Somali people before independence.

The strength of the pro-Arab attitude in Somali society was evidenced by the fact that Israel was 1960 compelled to withdraw its acceptance of an invitation to attend the independence celebrations of the new Somali Republic following a public uproar. To date, Somalis are staunchly pro-Palestine and anti-Israel with the emotionally captivating “Israel” song composed in solidarity with the Arab people during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, frequently making a hit whenever Israeli-Palestine tensions resurface.

In the decade and a half following independence, a wave of Arabization took effect in Somalia. Somalia’s foreign policy shortly after independence tilted towards the Soviets courtesy of influence from Arab foreign policies. This identity merger never disappointed the Somalis as their new Arab allies, particularly Egypt and Iraq, generously contributed to the building of the toddling Somali nation. Military training and scholarships came in handy from Cairo and Baghdad not to mention financial support from oil-rich countries. Gamal Abdel Nasser became a revered figure and his ideals source of inspiration in Somali society. Gamal’s cherished personality is rooted not in Egyptian aid but in the resonance of his ultra-nationalism stance with the militant Pan-Somali appeals. He is the most popular foreign figure in Somalia with educational institutions named after him.

The accession of Somalia into the Arab League on February 14, 1974, marked the Arabization period’s climax and the Somali people’s total detachment from their African identity. Speaking on that occasion, foreign minister Omar Arteh remarked that Somali people “were longing for this day.” This was echoed by President Siyad Barre who cited “historic association and common adherence to Islam” as the reasons for joining the League. But behind these thinly-veiled reasons, Somalia was courting Arab money and moral support for advancing the Pan-Somali appeals at a time when President Bare’s generals were contemplating plans to invade Ethiopia and take the Ogaden.

Decoupling from the African identity, however, did not lead to the full embrace of the Somalis by the Arab race, and thus, Somalis found themselves in a confusing state of belonging perhaps comparable to a “torn society” – from Samuel Huntington’s description of “torn countries” in his Clash of Civilizations.

New realities and inevitabilities

From the unexpected signing of the Camp David Accord in 1978 by Egypt, the militant Arab nationalism that from the beginning appealed to the Somali people had been dealt with a bloody nose. Decades later, several Arab nations are following the Egyptian example and as a result, a series of Arab-Israel normalizations under the auspices of the Abraham Accord are picking pace. Former Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid described this new wave of normalizations as embracing the “Connectivity Statecraft” or CS type of diplomacy. That is to say, countries do not always have to be completely like-minded or agree on everything, but instead, can choose to work together on areas of common interest while they disagree or even clash in other areas. While this is smart diplomacy of its kind, it however shows that an ideology as rigid as that of ultra-nationalist Nasserism can be revisited and bent to suit the fast-changing global environment.

It is prudent for the Somali people to diligently read this latest Arab-Israel rapprochement. Visibly, the militant nationalism that bound the two peoples together for several decades has been quietly abandoned by the ‘big brothers.’ And that lets us ponder if the Arabian Peninsula any longer holds ideological appeal to the Somali people. In the absence of such, let’s ponder about other next-best alternatives which can continue charming the Somalis to remain pro-Arab. Alternatives such as technological advancement, democracy, and good governance. With clearly no such alternatives as well, a re-evaluation of the pro-Arab orientation and exploration of other avenues is an urgent duty for Somalia policymakers. The rupture of the ideological cord, therefore, presents Mogadishu with an array of alternatives to reshape its decayed foreign policy orientation.

One such alternative is the Africanization of its foreign policy by seeking economic and social integration with the greater African continent using the flourishing East African Community as a corridor. Similarly, alignment with South Africa which has recently been positioning itself as the Core State of African civilisation, adds weight to the Africanization efforts of Somalia’s foreign policy. As a member of the BRICS bloc that is built upon the idea of equality and mutual benefit, a healthy economy and home to a significant number of Somali businesses, SA is a real deal at this juncture. Not only does moving to integrate with African economies guarantee social progress but also redeems the long-lost African identity of the Somali people. Most importantly, EAC and SA are envied democracies from which Somalis can borrow a leaf. In turn, Somalia can gamble on its vastly enterprising and business-savvy people as well as strategic ports to compete with the few established ports connecting to the interior.

Overhauling the current foreign policy premised upon keeping Somalia under the armpits of the rich Arab nations is urgent. This entails renouncing the invented identity that has since reduced Somalia into an Arab satellite state. Inject a new sense of spiritedness by diversifying relations and adopting a robust foreign policy, one that serves the nation’s interests best. Achieving this requires sacrificing greed and personal gains for the greater good and the long-term betterment of the Somali people. The current emotion-laced, impulsive and unilateralist foreign policy inherited from the dictatorial regime, which is incongruent with the realities of a multipolar order, should be jilted. This starts with mustering a decent pool of intellectuals to chart a new pathway to a grand and comprehensive foreign policy. Such a kind of policy remedies much of Somalia’s domestic predicaments that stem from foreign meddling.

Arab support before the collapse of the Somali state served as a tool for pursuing grandiose developments and realizing Greater Somalia in exchange for the latter’s support of Arab causes on world stages. Since 1991, the ground has shifted completely to disfavour the Somalis. Cash flow from the Arabian Peninsula is the biggest source of instability; funding proxy elements, bribing politicians, fomenting political crises and deepening clan cleavages. The Geopolitical tussle between Qatar and the UAE over the country in the past decade is a grim reminder of how Somalia has been relegated to the status of a kickball spinning between two goalposts. To remedy this unjust imbalance, it is paramount to reach out to East Asians, Russia, India and Brazil while also solidifying existing relations with Turkey. These countries are the pivotal forces of a multipolar order which can provide a means to offset Arab domination.

Iran has amassed a power of global reach and emerged as a force to reckon with. Its tough theocratic stance that envisions supplanting Western presence in the Middle East and the Muslim world is registering initial success considering Arab monarchies have already opted for bandwagoning. Mogadishu should as well work on cosying up its diplomatic relations with Iran and depart from the Arab-inspired hostile policy towards Tehran and its regional allies. A staunchly pro-Iran Houthi government in Yemen, which is more than a reality, means Tehran has successfully driven a wedge between Somalia and its historical Arab allies. Predictably, Yemen is poised to become Tehran’s new stepping stone to penetrate the African continent. Somalia can capitalise on its strategic location as the gateway to the continent and seek security cooperation with Tehran. Sidestepping Iran at this crucial moment invites backhanding policy, further aggravating Somalia’s current security challenges.

For the time being, normalisation of relations with Israel should be avoided. Doing so would likely elicit an irresistible emotional fury from the public which extremist elements could aptly utilise to discredit the legitimacy of the government and may further plunge the country into chaos. Ascribing to a flawed policy inconsiderate of public opinion could be as disastrous as the 1981 Cairo scenes. Romanticising with Somalia’s western and Northwest neighbours does not add an ounce to the country’s quest for political and social recovery. Countries characterised by rigid and oppressive regimes, absolutism, and titular institutions are setting a bad precedent for Somalis. Their embrace only invites backwardness and embodies similar tendencies at home. Traces of insatiable greed for imperial ambitions are still discernible from the Western flank which renders nugatory any attempt to open a new door of reconciliation.

Finally, an initiative should be taken by the Somali media, academics, politicians and intellectuals to enlighten the society. This entails arousing consciousness which is a step in exposing the public to the benefits, risks, challenges and conflicting interests of global actors as well as the geopolitical factors at play. Politicians particularly should dedicate a substantial part of their political engagements to global affairs instead of keeping the public preoccupied with narrow and divisive domestic affairs.

Aden Ismail

Email: aden.mohedi@gmail.com

Leave a Reply