By Shoki Hayir

I am a child of the Somali civil war. I was born in the early 1980s and my first political memory of any consequence is of being very afraid. Fear is not a crime in warzones but a consequence from bad political memory and a trauma for innocent children facing compelling circumstances, survival, and life challenges. This is the narration of an untold story of a child who remembers his last day at ALLAHIDA(the Egyptian primary school) near the presidential palace of Villa Somalia as the fighting erupted unexpectedly one day in Mogadishu early 1991 forced students to go home and never return.

As a child, I had no idea what was going on. I remember that last day of school, I had to walk home myself. What was also challenging was to find my way home because my mother was at work and my father was in Saudi Arabia. My other two older brothers were also at school but a different one (Yaasiin Osman school). Relatives later picked them up whom also happened to have their children at that school. For me, it is still a miracle how I reached that day home safe and sound. It is something that stayed with me till this day. Looking back now at the start of the Somali civil war, I can see that I had lived through a very difficult time in my life. Almost thirty years has passed now, but still today terror only seems to produce more terror in Somalia. My generation had already reconciled itself to growing old in the fearful paralysis of the Somali civil war.

The collapse of Siad Barre’s regime and the subsequent political turmoil that followed, led to a situation in which the deconstructive interrogation of Somalia’s shared history and identity became a fact. Since 1991, Somali history has been subject to many contestations and critical (re) interpretation of the remembrance of Somali civil war as a memory of shared experience. The historical narratives produced are much more disturbing and dangerous within the Somali society. This rather new ‘’historical truth’’ became an easy target for political manipulations. Seen from the past, Somalia’s shared history and identity were created through various events in pre-and postcolonial era: partitions, wars, the Siad Barre’s era and the civil war. All of these events shaped at some point in history the Somali attitudes and the collective memory of the Somali society.

The struggle for historical collective memory

Each year, there is a repeatedly heated debate among the Somali people on the occasion of October 21st, resulting in memorial consciousness of the Somali society. The need to remember often actively competes with the equally strong pressure to completely forget. However, these remembrances and narratives about the past extoll some groups, devalue others by transforming their differences into justifications. This creates either acceptance or confrontation of the alternative stories produced by the excluded. For instance, October 21st is contested date, which clearly created proponents mainly clan affiliates and associates of Siad Barre and opponents anti-Barre regime mainly due to suppression and crackdown. These constructed and contested narratives perpetuated divisions and, caused intense clan cleavages.

The generation after 1991 became the victim of that contested history. But this time, that history created a generation brought up in a diet of antagonistic memory. I have spent much of my life sorting out my experience of the Somali civil war and the impacts it had both on my family and in the wider Somali society. Over the past years, I have found about the meaning and the connotation of war and memory. As Viet Thanh Nguyen (2016) says ‘’all wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory’’. The Somali war could prove this claim. The entangling between war and memory have become commonplace after the disaster of the 1988/89 in northern parts of Somalia which resulted in the birth of Somaliland.

The problem of war and memory raises complicated questions. How do we remember war in general terms and how that war particularly shaped our life? For instance, the Somali civil war is remembered differently in Hargeisa and in Mogadishu or elsewhere in Somalia. For the citizens in Somaliland, the civil war represents the violent destruction of Siad Barre’s regime and the subjugation of the people from the northern parts of Somalia. The horrific and the mass killing of 1988/89 by Barre’s regime justify to a certain extent the existence of Somaliland as a separate entity from Somalia. Even though in reality, there was never a war between north and south of Somalia.

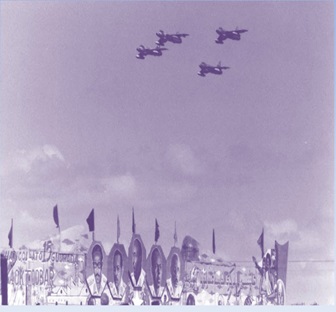

The Somaliland citizens wave their flags, vote and carry all the duties and rituals that affirm its existence. This is the distinct identity of the war and the features to remember the war produced discrete events. One of the most visible monuments to remember the war in Somaliland is the airplane at the Freedom Square in Hargeisa. It commemorates the victims of the aerial bombardment and has become a lieux de memoire (places of memory), the sites of memory in modern times as Pierre Nora says. The people in Somaliland created this particular site Lieux de memoire through the past thirty years and tell the inhabitants of these sites to remember the Somali civil war through places like this.

In the south and central Somalia, the fall of Siad Barre’s regime created both political and power vacuum, which resulted in local civil wars that have (re) shaped the historical memory of the south and central Somalia. Different interpretations of the Somali civil war exist in the tradition of the south and central Somalia. But it is not primarily a historical construction. The definition of Somalia’s shared history has limited relations with Siad Barre’s era. It is no longer an issue in the south and central Somalia. The prolonged civil war and the conditions in the south and central Somalia forced some ordinary people (especially older generations) to sympathize Barre’s era and long for him even though not being his affiliates or associates (just a nostalgia for those days). While in the northern parts of Somalia that almost similar memory of Somali civil war has purely become a private phenomenon and the last epitome of the unification of memory and history.

Coming back to the heated debate on October 21st, and the memory of the Somali civil war raises significant questions; how do we organize our past? And how do we create a bond of a remembering society with its history? October 21st is just one of the many contested narratives in Somalia. These narratives also undermine the search of a state in Somalia and pose whether the process in search of a Somali state starts with the remembrance of the war and the establishment toward just memory, forgiveness and the healing of all the wounds that inflicted the war. For forming a new Somali nation, people need history and this history requires ‘’a compass point’’ as said by Pierre Nora (1998) where people can identify their history and openly state their views. How do we form a national image and, a feeling of belonging to one nation? A shared historical path with mutual historic figures and heroes that every Somali individual gives the feeling of equality and unity which can lay the foundations to form an active nation state.

The need for a new civic nationalism in Somalia

There remains a considerable debate among the Somali people about the current approach to Somali problem and notably to the extent this approach can lead to the revival of the Somali state and eventually result in political stability in Somalia. While the Somali people formed many different identities over the past three decades, it is the Somali national identity, which can provide the primary form of identity and belonging. The revival of the Somali nation should begin with a new civic nationalism. Regardless of the differences, Somali people should subscribe to and envisage the Somali nation as a community of equal, right bearing-citizens, united in patriotic attachment to a shared set of political creed, practices and values. This civic nationalism is based on the merit principle. It vests sovereignty in all of the people and unites Somali people by a civic rather than a tribal definition of belonging.

This civic nationalism should bond the Somali society together not by a common tribal affiliation but by a law and law-abiding society. The absence of common shared memory and civic nationalism in the current discourse causes intense divisions and continue to remain divisive. Since Somalia belongs to one of those countries that have bitter memories of civil wars, the Somali national identity has been contested and damaged by the conditions of both bad experience with central authority and prolonged civil wars.

What Somalia has lost in the past three decades are the fundamental norms and values that once connected them as a nation and gave them a sense of belonging to collective identity and common shared history. At root, this is because when a given nation membership is salient to us, we act upon the particular norms, beliefs and understanding associated with the relevant self-category. In other words, only those who identify together can mobilize together. The coordination of actions that is shared through collective identity and shared historical past is a source of empowerment: the (re) interpretation of the past serves to define the present and to mark out the future. It provides the ability to pull together to overcome obstacles and to achieve collective goals.

Shoki Hayir

Email: [email protected]

—————-

Shoki Hayir is a teacher based in the Department of Political Science, Maastricht University. He is also a doctoral researcher at Radboud University where he is affiliated at the Centre for International Conflict Analysis and Management (CICAM).

We welcome the submission of all articles for possible publication on WardheerNews.com. WardheerNews will only consider articles sent exclusively. Please email your article today . Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of WardheerNews.

WardheerNew’s tolerance platform is engaging with diversity of opinion, political ideology and self-expression. Tolerance is a necessary ingredient for creativity and civility.Tolerance fuels tenacity and audacity.

WardheerNews waxay tixgelin gaara siinaysaa maqaaladaha sida gaarka ah loogu soo diro ee aan lagu daabicin goobo kale. Maqaalkani wuxuu ka turjumayaa aragtida Qoraaga loomana fasiran karo tan WardheerNews.

Copyright © 2024 WardheerNews, All rights reserved