By Muhumed M. Muhumed (Khadar

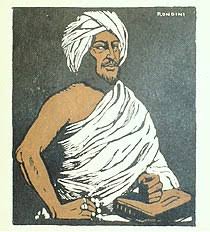

“No character in recent Somali history has drawn so much attention from both foreign and indigenous writers as the Sayyid Mahammad ‘Abdille Hasan, known in colonial literature as the ‘Mad Mullah’”1 writes the late Prof. Said S. Samatar. Therefore, given the eminence of the Sayid Mohamed’s character in the Somali history, it should not be unexpected to come across new analyses of his life and struggle and that of the Somali Dervish Movement a century after the crumble of the Dervishes as well as the death of the Sayid. Although numerous writers simply narrated the history of the Dervishes and the Sayid, few others conducted an in-depth analyses of the rise and fall of the Sayid, his personality, leadership style, and what led to the failure of his struggle after 21 year-long insurgency.

Rashid Sheikh Abdillahi “Gadhweyne”, a prominent Somali author, published his book “Qaran iyo Qabiil: Laba Aan Is Qaban”2 which roughly translates to “State and Clan: The Incompatible Two” in 2018. The book, a monumental work in the Somali literature, deeply addresses fundamental questions regarding the political and traditional reality of Somalis, nomadic pastoralists in particular, and how their traditions and, society and clan structures are incompatible with the modern state. Somalis were a society without a state (higher authority), or in other words, lived in what Thomas Hobbes refers to as ‘state of nature’ until the colonial powers arrived in the nineteenth century. Since independence (in 1960), Somalis have been struggling to successfully reconcile between the clan and modern state.

The aim of this article is to summarize Abdillahi’s analysis of the struggle of the Sayid Mohamed Abdille Hassan and the Somali Dervishes Movement between 1899 and 1920, for which the author dedicated a chapter of his book. Sayid Mohamed commenced his armed struggle in the Eastern part of British Somaliland, a Dhulbahante land (his mother’s clan). His movement soon became strong and grew rapidly due to a number of factors: British administration was concentrated in the coastal towns and was not strong in this part of the Protectorate; Dhulbahante support based on his maternal relationship with them; the support of his own clan, the Ogaden and most importantly the Sayid’s personality – a charismatic religious cleric, outstanding poet, and warrior. Moreover, Clan fighters were attracted by the power of the Dervish Movement and the material gain – the wealth, primarily livestock, accumulated through robbery, looting, and (illegal) forceful confiscation.

The Sayid initiated his movement in a society living in a state of nature, divided as clans and struggling with killing and revenge killing, camel looting, and continuous fighting and hostility among clans. Neither Sayid Mohamed united the divided clans under his leadership nor denounced their evil actions. He rather assimilated into their system and became a Somali nomad with power who, since he could not utilize the power wisely, tended to act like a dictator – for instance, the Sayid always had the final word of executions using his famous statement “remove him from my sight”; although there was a judge at the Head Quarter (xarun), he did not have judicial independence. The Somali society is often characterized as an egalitarian society but this notion holds if and only if the clans have equal power. As soon as one clan accumulates more power, they suppress and dominate the other clans – the reality of the Somali society in the last three decades can practically explain this best. Sayid Mohamed and his movement were not an exception.

Sayid’s rule was based on the notion of “you are either with us or against us” – even if it sounds like a contemporary concept. Clans who did not follow him or their fighters did not join his army were portrayed as apostates (or infidels) and they were enemy; therefore they should be killed, their livestock looted, and to some extent, their wives married off to the Dervish soldiers. Given their aforementioned behavior and actions, the Dervish Movement more or less became an additional (rival) clan to the existing Somali clans.

Abdillahi examines a few cases revealing how the Dervishes acted like the other Somali clans. Sayid Mohamed mobilized his first strong army in Burao and despite targeting the Ahmediyah Order in Sheikh, his army, keeping history and hostility between the rival clans in mind, attacked the Habar Yonis clan (of Isaaq) and looted their camel. Similarly, when Garad Ali Garad Mohamoud of Dhulbahante was killed, most of the Dhulbahante soldiers defected from the Dervishes and Sayid Mohamed had to move to the Ogaden land. He mobilized a strong army there, fought with the Ethiopian forces, and recovered thousands of livestock looted by them earlier. Bewilderingly, shortly after these clashes with the Ethiopians, the Dervishes attacked the Idagale clan (of Isaaq) and looted 2000 camels (this attack is also known as Dayah Werar). The fact that the Sayid’s bodyguards, whom he relied on for his safety, were from the marginalized minority clans reveals that he did not trust the majority (noble) clans. Although men with similar leadership tactics would do the same, we should not rule out the role of the hostility and mistrust among the rival clans.

Sayid Mohamed was a nationalist a figure, religious clerk, warrior, and exceptional poet who fought against the colonial and occupying powers. The primary objective of his struggle (or jihad according to him) is widely agreed but the approaches and results of the struggle could be debated about. Abdillahi lists a number of opportunities which had the Sayid seized, his struggle would have been more successful: he could bring peace among the warring clans; respect the agreements between the British and the local clans which avoided further attacks from the Ethiopians; consider the significance of the livestock trade for both the British Administration and the clans; avoid the antagonism with the Qadiriyah and Ahmadiyah orders.

The argument and the concept of this article is that of Rashid Sh. Abdillahi. Whilst we covered a small part, Abdillahi’s study is a groundbreaking and hugely contributes to the literature of the Somali history, political science, and sociology. Since the study is now accessible only to the readers of the Somali language, I urge the author to consider publishing his study in English, either as a book or as an article or series of articles.

Muhumed M. Muhumed (Khadar) is the author of “Kala-Maan: Bilowgii iyo Burburkii Wadahadallada Soomaalilaand iyo Soomaaliya”. He is a researcher based in Hargeisa, Somaliland. He can be reached at: [email protected]

—————–

Reference

1. Samatar, S. S. (1982). Oral Poetry and Somali Nationalism: The Case of Sayid Mahammad ‘Abdille Hasan (No. 32). Cambridge University Press.

2. Cabdillaahi, R.S. (2018). Qaran iyo Qabiil: Laba Aan Is Qaban. Ponte Invisible (Redsea-Online), Hargeisa.

We welcome the submission of all articles for possible publication on WardheerNews.com. WardheerNews will only consider articles sent exclusively. Please email your article today . Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of WardheerNews.

WardheerNew’s tolerance platform is engaging with diversity of opinion, political ideology and self-expression. Tolerance is a necessary ingredient for creativity and civility.Tolerance fuels tenacity and audacity.

WardheerNews waxay tixgelin gaara siinaysaa maqaaladaha sida gaarka ah loogu soo diro ee aan lagu daabicin goobo kale. Maqaalkani wuxuu ka turjumayaa aragtida Qoraaga loomana fasiran karo tan WardheerNews.

Copyright © 2024 WardheerNews, All rights reserved