By Faisal A. Roble

Mr. Mahamoud Gaildon’s reminiscence of his rather positive encounters with a number of Jigjiga boys, including this writer, in Hargaysa and at Camuud Secondary School in the 1970s, is a symbolic narrative of a bygone era. My own rumination of this subject comes at a time when Abdi Adan Qays (Qays), one of the greatest Somali poets in modern history, along with Khadra Daahir Cige, the queen vocalist in the Somali speaking world, concluded a visit to Jigjiga in August of this year. It took an emotive Dhaanto sung on behalf of Khadra to bring her and the rest of the delegation into passionate tears.

As to Qays, he was an early source of a political awakening for my generation, thus his worthy visit to Jigjiga 40 years later says a lot about the connectivity and organic linkages among Somalis no matter under what jurisdiction they live.

The Jigjiga boys are indeed the product of special socio-political circumstances of the Horn of Africa region of the 1970s. In this essay, I would rather take the conversation few years back and quickly glance at the making of the minds of those boys revisited by Gaildon. I will do so in two parts. Part one is a background to some of the literary sources that influenced them, while part two would deal with how they became revolutionaries and the subsequent dashing of their patriotic spirit by the Barre regime.

Part I: The Gathering of the Perfect Storm in the Region

The year 1972 represented the confluence of westernization and an impending peasant revolution in the Horn of African’s most populous country, Ethiopia. On the one hand was a minority and ostensibly rich Amhara feudal class that enjoyed anything western (music, cloth, cars…) to quench its insatiable consumerist appetite. On the other side were the multitudes of mainly peasant societies that wanted change, a transformational change of the Ethiopian polity, including the dismemberment of what one revolutionary called “prison of nationalities.” No one group wanted change in Ethiopian more than Somalis in the Horn of Africa region.

In that year (December 1972) students both at the then Haile Selassie University in Addis Ababa and in the country’s secondary schools begun a national commemoration for the death of two revolutionary student leaders – Tilahun Gizaw and Martha, who tried in vain to kidnap an Ethiopian airplane demanding to go to Algiers – a mecca for more radically inclined student revolutionaries.

Soon after, the student riots expanded like a blaze of fire to all regions and that never stopped until the Dergi came to power in 1974, after which time all junior high school students or higher were ordered by degree to participate in a National Rural Campaign. One of the goals of the campaign was to quell the mushrooming of student activism.

However, sending students to the rural areas was a blessing in disguise for those who wanted to organize for a cause greater than urban riots, and a curse for the Dergi who wanted to isolate students from the urban sector. In the rural areas, idealistic high school kids not only cast away their love affair with western music, but begun reading heavy literature, mainly leftist and subversive materials, side by side with highly politicized university students. In addition, urban boys and girls for the first time came in close contact with peasants and the masses outside cities.

Not only was this a source for more understanding about the question of land tenure, but it gave urban kids a reality check of how the other ninety-nine percent lived. Unbeknown to the Dergi, the campaign radicalized the entire society, and some of the boys who participated the campaign later on brought the culture of reading subversive literature back to Jigjigia – more on this subject in part 2.

Subversive Winds from the East and the Making of Minds

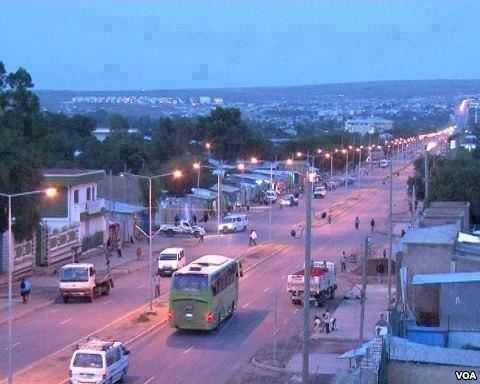

To the east was Hargaysa, only about 196KM ( 121 miles) from Jigjiga, where our kith and kin were suffering under an autocratic military ruler (Siyyad Barre), who was mercilessly cracking down on civil servants, poets, singers and artists.

Unlike in Ethiopia, Somalia’s urban middle class (if there was any) never developed a revolutionary culture to combat oppression, but always looked social issues within a clanist prism. One Ethiopian leftist who was deported back said during his court proceedings that “he could not find a single progressive intellectual even during light in the entire Somalia.”

That does not mean all social groups acquiesced with oppression. At least poets in the north and northeast challenged Barre’s government early one. Qays’ songs, dark songs that appeared to be both metaphysical and subversive, and sung by none other than the late Mohamed Mooge, dominated the airwaves of the teashops of my town’s main street.

Songs like “Aduunyoy Xaalkaa Ba,’ a song that would often be sung by the youth during afternoon school breaks, in hindsight foretold the impending gloom, destruction and impoverishment of the Somalis. Or, “hayi fudud habeen kaan lahaa bay hubsiimadu haboonayd,” was an obvious registration of the North and northeast’s cry for equality within the context of the Somalia union. But once again Qays’ words fall on deaf ears.

In the early hours of each morning one would not miss the blasting of music coming from the trio restaurants that dominated the street frontage of the main street of Jigjiga. Two of these joints were owned by relatives of my father who had returned from Arabia, and the other larger joint, known as Jibbax which sat directly opposite to the decrepit former Somali Youth League (SYL) Headquarter of the 1940s, were the center of the city’s youth culture.

A more powerful but silent cry for what was wrong in Somalia at the time was expressed in another powerful song by Abdi Adan Qays: “Aakhiroy Halkee baad naga Xigtaa:” One needs to listen to these songs with keen interest in social issues and you could easily capture the painful context that prompted the song writer – sense of feeling of alienation and a nation headed to its death knell:

Inta gabadh xishood tiyo

Wiil xariir ah kugu maqan

Ama geesi kugu xidhan

Xaadi way kabadate

Xidiga cirkee sare

In aad koox ka mid ah tahay

In aad hoos u xulantahay

Ama xero ku leedahay

Maanu helin xogtaade wali

Aakhiroy xagee baad naga xigta

No sooner did this song hit the airwaves than the north and northeast face more clampdown of its urban social group. Consistent with Qays’ words, many people were sent away to unknown jails such as Laanta Buur in the South and to other far away prisons. (As would be discussed in part two, about four of the Jigjiga boys would be sent to Laanta Buuraa prison where they would meet all kinds of prisoners). Also, about sixty civil servants were labeled anti-government only to summarily be fired without any severance package for the years they served their country, most of whom came to Jigjiga.

One remarkable person who was a victim of the early crackdown on the middle class in the north and northeast that I still remember was Ina-Cadaane, a thin, light-skinned and fairly well educated former manager of the cigarette importing agency. Ina-Cadaan settled in Jigjiga and stayed politically engaged, where he would often talk in vain to unsuspecting students about Barre’s autocratic nature.

A more risk-averse Hadrawi for the first time joined the embryonic dissident literature with a response to Qays’ Aakhiro with Araxmaan siday tidhii that goes this way:

Waa ooman hawdoo Waa guri abeesoo

Adeeg weeye hoosoo Abatakh ku yaaloo

Waa iil madow oo Rabbigay adoomaha

Kaga aar gutaayoo Wa laga arooraa

Iradaha Xabaashoo Amba maayo ruuxii

Qabri lagu adkeeyee Aakhiro Cabdow

Waay Aasantay, ilkay Jjirtaa

Aakhiro Cabdow, Ambatayoo luntoo

Uurkiyo Laaxaha Awrkii cirkay

Ku ag Xidhan tahee Dadku yuu ku eedayn

Ha dhex gelin ummuuraha Arag maqal warkana ood

Most of the dissidents from Hargaysa who came to Jigjiga either to permanently live or pass through gathered at Ali Nuur Suldaan Haashi Elmi’s house. Because of his familial relationship with Ali Nuur Haashi (GBHS), my late father will always get papers (damiin) for the dissidents.

Unfortunately, Somali elites never had a public conversation of whether the clampdown on the north and northeast represented the beginning of what became an official crackdown on civil rights in the country. Now we know, though, that the descent of Somalia to the abyss begun not in 1988 but way back in the 1970s when Barre decided to mistreat northerners and northeasterners.

The only social class that attempted to initiate public conversation on what the military regime was doing to the country and to its people in the early parts of the 1970s was the poets group. Said Salah, the late Hashi Dhamc Gariye, Qays, Mohamed Hadraawi and other luminary poets joined the questioning of the injustice of the Barre regime. Such discourse is archived in the epic poems of “Siinlay,” “Siinlay” established a poetic genre that sought to inject meaning into the eclipse and the suffocation of free speech which was the hallmark of Barre’s rule.

Common to my generation at the time, by the time I was tenth grade from example I could recite all the verses of “Siinlay” with ease and dig the coded message which could at times be pan-Somali politics, or a regionalist grudge.

When Love Songs convey Political Message

Another luminary dissident of the 1972 exodus was the Mogadishu-born singer, Ahmed Rabsha. It took no time for Ahmed Rabsha to establish temporary residence in Addis Ababa; he joined a team of veteran Somalis and Arab Somalis who were already established in the music/media business in Addis (Cayni Nuux, Ina Xuseen Giire, Muxsin Abddall, Abdala Faadil, and Nuradiin Abdalla Nuuradin who left for Somalia only few years before).

Rabsha’s love songs were sensational and were easily embraced by the elite in Addis Ababa. His beaming image and his easily recognizable looks of mixed heritage made this young Somali a household name to both Somalis and non-Somalis in Addis Ababa and beyond.

Along with other Ethiopian singers, the ruling elite in Addis had its own plan – to divert the youth from revolutionary activities to music, mainly to western music and sports, and Ahmed Rabsha’s music came handy.

Ethiopian girls in particular, especially those who mainly attended foreign schools in Addis Ababa (English School, American School, and Greek School) instantly fall in love with the young novice Somali singer. Both his looks and his charm appealed to the daughters of Addis Ababa’s elite.

Rabsha instantly captivated a large audience among the elite. School break time conversation by girls from elite families in Addis would often be dominated by the cult-like admiration for this young and left-handed musician.

Armed with nothing except his guitar (cuud) and his melancholic, prickly yet soothing voice, Somalia’s Ahmed Rabsha was the best Ambassador a nation could have – earning respect for one’s country even from its enemy. By filling the black and white TV screens of Addis with Somali songs, Rabsha was earning fame and respect for Somalia, despite the dictator’s behavior back home. I still vividly remember when in 1973 or 1974 a daughter of a high ranking young girl whom I met through a mutual friend, the late Ahmed Cumar Samatar (Saldo), asked me if I can get her a tape of Ahmed Rabsha’s.

One song that left a lasting influence on my group is: “Axadii” with lyrics such as:

Waa la ii adimay Axadii sidaan

Kuu eegayee Arageeda taan

Ku ildoogsadaay Ma ilowsantahay

Axdigaad martiyo Meeshaad i tidhi

Waan imanayaa

Unlike the boys and girls in Addis, Rabsha was seen by Jigjiga boys, those boys that Mr. Gaildon would be meeting some years later in Hargaysa and at Amuud, as an ambassador of what was good about his country of 1972 – that is before Barre would embark to annihilate what could have been a beautiful republic. Rabsha’s songs meant more than mere love songs; they represented as if the “the bell tolled” for freedom and reunification of the Somali nation.

The ability to convert love songs into political message: (a) is embedded in the very nature of the Somali spoken word (hadal waa margi oo kale), and (2) oppressive conditions such as that of Jigjiga and Hargaisa in the early 1970s are ideal conditions to do so.

In the lyrics “Waa la ii adimay axaddi Sidaan kuu eegayee,” or, when translated loosely, “my waiting for you in vain lasted till dusk prayer time arrived,” was translated by the Jigjiga boys as if it conveyed a message of Somalis waiting for the dawning of freedom. Alas, the disappointing no-show by his girl meant to us the challenges awaiting us to work towards the reunification of Somalis.

The Ethiopian government ostensibly encouraged Cairo-produced record players to be imported to Jigjiga, and thus Axmed Naji songs soon hit the air waves. The city was awash with gramophone players, one notch higher than stereo players (Shariig). The most popular song that was listened to on gramophone players, some of them as large as cupboard, was this:

Ma sidii Ayuu baan

Isla aamusaayoon

Waxa uu yahay

Ayaankay iimaansadaayoon

Samir Eebo qaataa

Mise qaramada midoobee

Xaqa hoos u eegaan

Arintayda geeya.

This song was fittingly political for the Jigjiga boys, simply because it hit the market when Somalia’s eminent Foreign Minister of the 1970s, Cumar Carte Qaalib, was making the case for Western Somalia’s independence. His visit to the Organization for African Unity (OAU) and the United Nations Headquarters gave this song the right impetus. With no difficulty, we translated it to mean a plea to the world community. We then collectively but clandestinely admired the genius of the Somali language, in particular Qays’ history changing hit after hit.

Rabsha left for Cairo sometime in late 1974 or early 1975. But he left us with positive impressions about Somalia. Nevertheless, he did so without ever publicly mentioning what made him leave Mogadishu and seek asylum in oppressive imperial Ethiopia. The next time I enquired about him was in 2010, only to sadly learn that he had passed away.

Abdi Adan Qays’ poignant song of “Xeebtaa Jabuutee Soomali laga Xaday, Hadii aan Xagaa tagay Xeerna maan jabine Maxaa la igu soo xidhay,” literally consummated the extrajudicial arrests, intimidation and harassment which the people of Hargaysa faced. In addition to many other affinities with the people in the north and northeast, the oppressive political culture we shared on both sides of the boarder cemented our bond that withstood multifaceted manipulations of the mind. We came to know not now but 40 years ago that Qays was killing two birds with one stone. Abdi Aadan Qays historic visit to Jgjiga commemorates two cities joined by blood, permeable boundaries and broad continuum for freedom.

Faisal A. Roble

Email:[email protected]

We welcome the submission of all articles for possible publication on WardheerNews.com. WardheerNews will only consider articles sent exclusively. Please email your article today . Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of WardheerNews.

WardheerNew’s tolerance platform is engaging with diversity of opinion, political ideology and self-expression. Tolerance is a necessary ingredient for creativity and civility.Tolerance fuels tenacity and audacity.

WardheerNews waxay tixgelin gaara siinaysaa maqaaladaha sida gaarka ah loogu soo diro ee aan lagu daabicin goobo kale. Maqaalkani wuxuu ka turjumayaa aragtida Qoraaga loomana fasiran karo tan WardheerNews.

Copyright © 2024 WardheerNews, All rights reserved