By Mohamed Garad

On June 8, 2019, the state TV of the Somali Regional State, SRTV, broadcasted semantically the best news that the people of the region have ever heard since the loss of their sovereignty in 1887. In the afternoon of this summer day, the TV delivered that national legislation which grants the people of the region a 50% share of the natural resources endowed in their land had been passed.

The reception of the news message placed the region’s people in a juxtaposition angel. Knowing the fact that their state is the home of at least 8 Trillion Cubic Feet of natural gas but consciously aware of the endless marginalization against them, the delivered message disrupted the cognition of the mass. They couldn’t believe what their ears were hearing, nor their eyes were watching. They couldn’t fathom how the empire that has been colonizing them for more than a century simply granted them a 50% share of their natural gas resources. “If Ethiopia is such a fair state, why have we been fighting with them for more than a century?” one asked on Facebook. In other words, the delivered news message created cognitive anarchism in the largely illiterate society, but the mass became largely skeptical not only about the news message but also about the integrity of their unelected regional administration.

Accordingly, this essay, which has two sections, addresses the validity of the broadcasted news message and related domestic laws in the first section while its second section examines the international frameworks under which any existing domestic rules and agreements should conform. In doing so, the essay reviews and analyses the country’s resources sharing laws and the economic significance of any publicly visible legislation and agreement regarding the share and production of the Ogaden gas resources. The impacts of the gas production on the environment, health issues, and political stabilities are NOT in the scope of the essay.

SECTION ONE: REVIEW OF THE NEWS VALIDITY AND RELATED LAWS

In the clearest words, the news that Ethiopian House of Federation passed a draft bill which “grants 50% share of the resources to the state in which the resources are founded, 25% to the federal government in which the producing state will have its respective share again, and the remaining 25% to the other states of the country” is false. Even though the Ethiopian House of Federation doesn’t have a legislative power to enact such laws, the house didn’t address the like of such matters. Instead, the House deliberated on budget subsidy allocation formula, a federal tool used for intergovernmental fiscal transfer and “revenue” collections to help member states fill their budgetary gaps.

This subsidiary budget formula has been in place for 22 years and is developed based on the assessment of population size, expenditure needs and revenue-raising capacities of states. It has been tried to revise in 2016 but become impossible due to a lack of accurate reliable data about the above decision factors. It was early May 2019 when the speaker of the house of the federation, Keria Ibrahim, was quoted saying the “existing budget allocation formula lacks fairness and clarity and should be revised based on right principles.”

Accordingly, the news which states a 50% share of natural gas resources were allocated to member states has no factual existence and legal possibility and therefore is a blatant lie. And even if the allocation of the subsidiary budget allocation formula grants regional states the reported tax revenue rates, these rates are budgetary in nature and will expire with the terms of the budget instead of being the law of the land. There is no single reasonable doubt that whatever tax revenue sharing papers Ethiopian House of Federation had passed on June 8, 2019, will expire before the full commercialization of the Ogaden gas resources.

However, since the phrase “revenue collection” had been in the sentences of what have been deliberated on, enough attention should be given to the clarification of the broad phrase of “revenue collection” and Ethiopia’s institutional and fiscal arrangements.

According to the oxford dictionary, the word “revenue” means “income, especially when of an organization and of a substantial nature.” Thus, in the context of government, revenue collection means the government’s activity of collecting money from all publicly mandated sources. These sources are broadly categorized into tax and none tax sources. Subject to each country’s tax codes and rates, the tax sources are income from taxes levied on the different types of taxes like individual income tax, corporate income tax, excise tax, value-added tax. The none tax revenue sources are income from fees to government services, the income of the government-owned enterprises, the central bank revenue and so on. Thus, the important question is how these various types of revenue sources are decided and shared in Ethiopia?

Ethiopia’s revenue sharing between the federal and member states is clouded by unfairness. The federal government controls 80% domestic revenue sources and 88% of all indirect taxes according to findings of Girma Deffere, a lecturer at Jima University. According to Art. 96 of the federal constitution, sources of import and export, the income of the employees on the federal government and international organizations, all types of federally owned enterprises, air, rail and sea transport, monopolies, stamp duties, federal properties, and wining lotteries are all exclusively given to the federal government.

Concerning the state tax sources, article 97 gives states the tax sources of income of state employees, land usufructuary rights, private minors, individual traders, traders carrying out business with in-state territories. However, article 98 of the constitution concurrently gives the federal and state the power to “jointly levy and collect taxes on incomes derived from large-scale mining and all petroleum and gas operations, and royalties on such operations.”

Other than the above constitutional fiscal arrangements and its predecessor, proclamation 33/1992, there is no any other law governing the share of tax revenues between the federal and member states. Therefore, any decision to share the concurrent power of jointly levying and collecting taxes on incomes derived from large-scale mining and all petroleum and gas operations and royalties which Ogaden gas resource is one of them requires new legislation from the Ethiopian House of People’s Representatives and possible may require some constitutional amendments.

Given the history and the current political condition of the Somali state and that of the country, the chance that the Ethiopian House of People’s representatives will pass legislation which grants a fair share of tax revenue to Somali state and other similar regions is very low if none existent. Therefore, even though this essay cannot fully rule out the existence of a budgetary formula which grants favorable tax revenue share to owners of Ogaden gas resources, THERE IS NO, without a single reasonable doubt, any tax law which grants the broadcasted tax revenue shares to the Somali state and the possibility to have such law is at their minimum level.

SECTION TWO: THE EXISTING AGREEMENTS AND THE INTERNATIONAL AND DOMESTIC FRAMEWORKS

In this part, the essay will examine the frameworks under which the stated budgetary formulas work and the economic impacts of any existing production share agreements about the Ogaden gas fields. Nonetheless, though this essay cannot verify the exitance of the budgetary formulas which grants a 50% share of the gas tax revenue to the Somali region, the essay assumes their exitance for assumption purposes.

Following the broadcasted news of June 8, 2019, to the surprise of many, the acting president of the region once more gambled the intellect of the mass. In an interview he gave to the BBC Somali, he reiterated the existence of the resource sharing agreement but has failed to use any specific terms. Using the broadest words possible, he states “a consensus was reached that 50% of the revenue generated from the gas, petroleum, and minerals of the country is for the producing regions,” which by default the Ogaden region is one of them. When the reporter asked him to specify what this percentile mean, the president slammed both the economic theories and global practices related to the matter and blindly claimed “internationally when a country and oil company agree, what’s calculated [ at stake] is the profit tax and it’s that tax what’s to be shared.”

While international realities are far from that the acting president describes, one should dig a little bit deeper to understand how oil and gas are utilized in the world.

Oil and gas resources are double-edged weapons. Countries which are rich in oil and gas can substantially benefit the resources and achieve higher living standards while “at the same time, the economic performance of many oil exporters has been disappointing, even to the extent of prompting some observers to ask whether oil is a blessing or a curse,” in the words of the International Monetary Fund, IMF. Among other factors, what makes the gas and oil resources a blessed gift of Allah or a curse beneath the earth’s surface are the political and institutional arrangements in which the resources are produced. Oil and gas resources produced in politically fair and stable institutions with good governance, transparency, and accountability usually lead to economic prosperity while those produced in lack of the above characters create economic curses.

As this essay is being written, Ethiopia ranks the 118th in the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, an independent global index which rates 126 countries of world by measuring the country’s performance of constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice, and criminal justice. Under such conditions, the Somali region is a territory occupied by such country during the partition of Africa whose people have been struggling for the right to self-determination ever since. Thus, the region absolutely lacks a genuine political institution in power. While it’s given that resource produced in such an environment to be cursed, the international context of the interface between fiscal policies and oil/gas productions which shows how benefits and costs are traced must be brought into the light.

Before the 1960s, the global oil market was dictated by colonial terms. Multinational corporations namely the seven sisters, owned by the colonizing global powers, had been monopolizing the international oil markets by setting both the price and volume levels as well as the conditions under which oils had to be produced. However, at the peak of the third world’s quest for independence, the UN resolution of 1962, (UN 1962: Res.1803), which granted the “right of peoples and nations to permanent sovereignty over their natural wealth and resources” brought an abrupt and dramatic change to the global oil markets as well as the role of governments in the oil industries. Six years after the adoption of the UN resolution, the organization of the newly independent countries, OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries), adopted a resolution, (OPEC 1968: Res. XVI.90), to maximize their oil revenues subject only to one constraint: the market, a factor economist call a distant slack variable.

Following the adoption of the OPEC resolution, despite falling prices in the Persian Gulf, “the governments’ take in the Gulf increased from 50 percent to about 75 percent” in the findings of Bernard Mommer, a leading economist scholar in the oil industry at Oxford Institute of Energy Studies. Mommer observes that this extraordinary success of the OPEC countries and the subsequent reaction of the oil producing and consuming countries of the industrialized western world towards the OPEC impacts, their former colonies, led to the division of the global governmental fiscal regimes in oil/gas resources into two extreme classes which may have many options in the middle: the liberal fiscal regimes and the proprietorial fiscal regimes.

Mommer asserts that each type of fiscal regime, the liberal and proprietorial, cannot be defined in a single law but rather their components are “actually found dispersed in different laws and rulings, and their beneficiaries may include municipalities, provincial administration and the central government.” However, the two regimes fundamentally differ in their definition of the ownership of the oil/gas resources and the purpose the state should serve.

In the liberal fiscal regime’s view which was developed to offset the economic impacts of the newly independent nations, the natural resource is “a none-property—a free gift of nature—or a free state property.” Thus “the role of the is that of licensing agency and regulator, just like other sectors of the economy and collecting standard state taxes” which are subject to the state of the economy and economic policy goals of the country, Mommer observes. The purpose of this fiscal regime is to “guarantee the companies free access to the natural resources as such and thereby, supplies consumers with oil at cost price,” in the Words of Mommer.

Accordingly, though the essay is yet to discuss the proprietor fiscal regime, the acting president’s declaration of “internationally when a country and oil company agree, what’s calculated [ at stake] is the profit tax and it’s that tax what’s to be shared” is just like the speech of the CEO of the Royal Dutch Shell calling for the abolition of the state ownership of the oil resources in 1960s. His assertion is a colonial approach which makes the Ogaden gas fields “a gift of nature” which is open to everyone who wants to exploit it. Instead of acting as a protectorate of the people’s resources, he’s acting as a foreign agent. By saying those words, he is for the position of Polly GCL, not for that of the Ogaden region nor that of the Ethiopian empire. But whether he said that because of misconception or was motivated by other none genuine factors remains to be seen.

Unlike the liberal fiscal regime, the proprietor fiscal regime, “reflects the national interest of the oil-exporting country,” Mommer observes. The governments of this fiscal regime act as the owner of the resource within the international economy. Instead of relying on the mercy of the entrepreneurial decisions of profit-oriented companies (domestically owned or foreign companies), countries following modes of this fiscal regime secure their peoples a proper “ground rent”, regular payments (annuities) made to the owners of the resource, in this case, the producing state.

To assure proper annuities for their countries, states employing modes of these fiscal regimes minimize their share of the various risks involved in the production of the oil to the lowest possible. Like any other business investment, these risks are inseparable from the extraction of oil resources. For instance, no one knows the exact amount of deposits to be discovered. Subject to the intensity of the exploitation, deposits could be depleted faster or slower. In addition, depressed markets could severely shrink the profit margin of the oil industry.

To avert all the above risks, states following proprietary fiscal policies levy annuities that reflects the size of the discovery, the intensity of the exploitation, and prices by first charging a ground rent per unit of output and then considering variations of prices and inflation into a percentage royalty. Thus, with fixed royalties, state and producing companies share the risk regarding volumes and share the price risk in the percentage royalties. In other words, states bear the risks associated with the volumes and prices, not about the companies’ profit margins. “Hence, at low volumes or prices, profits may disappear but not ground rent,” in the words of Mommer. Therefore, it’s after the interest of the state is guaranteed in the production of the gas, do various taxes including the profit taxes come into play.

Sadly enough, the absence or the application of the above mechanism is so far irrelevant to the people of Somali Galbeed/ Ogaden region, the sole owners of the gas resources. Since the blueprint used for the expression of such an arrangement is the contract between the Polly GCL and Ethiopian government which is already in effect without the people’s consent and consultations, presence of any provisions that states the above concepts or their absence has no benefits for the people of the region. But what’s amazing are the answers to the questions of what will be the 50% share of the revenue that the regional administration declared, if there will be been no profits? Will the people of the region get zero while their most valuable resources are being depleted? How to verify that there had been no profits generated from the gas extractions in case the Poly GLC claims so? These are the questions which the regional admiration doesn’t have their answers.

However, to continue the paper’s analysis, even though oil annuities are based on prices and volume levels, surveillance and financial transparency issues which are beyond the capacity of the normal state bureaucracy come in to play at all levels of the chains of oil productions. One mechanism to solve this state limitation is the use of national oil companies, (NOCs). As a window on the oil industry, Mommer asserts, “NOCs can narrow significantly the information gap between the international companies and the ministries.”

To realize the objective of the NOCs, production share agreements (PSA), contracts between the international companies and the landlord state stipulates the names and the shares of the NOCs in the venture. These NOCs in the venture participate in the day to day operations of the oil productions and get full access to all relevant information and take part in the management decisions. In doing so, the NOCs serve as a watchdog of financial transparency agents and collectors of state annuities for the landlord state. They are the real managers of the oil productions and limit the mandates of the international complies only to service level.

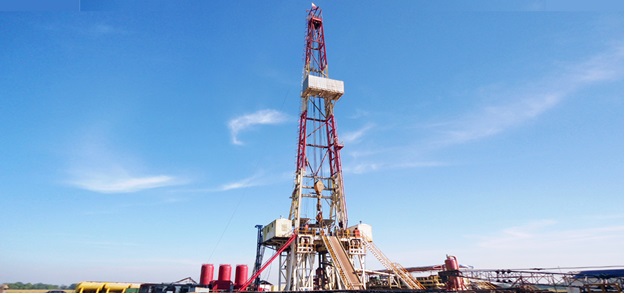

However, how the Ogaden gas resources are being produced defies this international standard. Since all its history, from the exploration stage to the current production stage, Ogaden gas resources has been a subject of a cover-up. Details of any contracts about its exploration or production stages were never made publicly visible nor consulted with the people of the region. The matter was exclusively between the Ethiopian government and international foreign oil companies. Nonetheless, currently, as Ethiopia doesn’t have any public owned national oil company, reported news states that the contract between the Ethiopian government and the Chines oil company, Poly GLC, grants 15% share to the Ethiopian government while 85% share is given to the chines company. It is largely because of this generous agreement that emboldened the Chines company to act like national oil company and subcontract “another Chinese company, China Oil HBP Group, to commission the Calub and Hilala natural gas fields in the Ogaden basin” for $313 million, as the Ethiopian journal, The Reporter, reports.

Thus, though it’s very hard to make any significant inference from the above abnormal arrangements without any further details, the senses of what’s apparent now shows that the Ogaden gas resources are being granted as “a free gift of nature” to a foreign companies and meaningful public ownership mechanism which guarantees the stated 15% share of the empire is even missing. So, when it comes to the people of Ogaden region, “the boat has departed a long time ago,” in the words of Faisal Roble.

To put in a nutshell, the production and exploration of the Ogaden gas resources lack one basic and fundamental principle to become a blessed resource: a genuine public institution in power. As far as that factor is missing, any agreement to explore and produce it is sinister in nature and doesn’t have any meaningful economic benefits to the people of the region. To prevent the resource from becoming new curses, efforts should be directed towards creating the missing factor. Since the land of this resource and its people are occupied during the partition of Africa, any agreements to exploit the resource must be framed in the spirit of the UN resolution 1803 (XVII) of 1962. As far as the broadcasted news of a 50% share of the revenue to the Somali region is concerned, the existence of such false news shows the higher degree of indignation against the people of the region.

Mohamed Garad

Email: mohagarad571@gmail.com

———————

Related Articles

– Laughing Hyenas: Red flags the new Somali Regional President should be wary of By Liban Farah

–Somali Region: A Battle ground for Democracy VS Domination By Faisal A Roble

–A Message to PM Abiy Ahmed By Mohamed Heeban

–The Ogaden question a perennial conundrum that preoccupied every Ethiopian leader but none got it right By Prof. Hassan Keynan

Leave a Reply