By Adan Makina

Editor’s Note: Taken from Adan Makina’s upcoming book “The Political Struggles of Sultan Deghow Maalim Sambul”, this chapter exposes the sufferings encountered by Mzee Ahmed Hussein who was almost sentenced to death by the British colonial Administration that reigned supreme in much of East Africa. Ahmed Hussein was arraigned in a court of law on trumped-up charges before a White judge for possessing unlicensed or illegal Berretta pistol in an era when Kenyans were subjected to extreme humiliations and treated with contempt by the colonial government. It could sound impossible to the first-time reader for a Kenyan-Somali to challenge a colonial judicial system by engaging a White Lawyer and have his freedom after a long legal tussle. Had Mzee Ahmed been found guilty by the court, he would have been “Hang by the Neck until Pronounced Dead.”

—————–

The first Somali in colonial Kenya to be arraigned in a court of law on spurious trumped-up charges was a man called Ahmed Hussein. Mr. Ahmed was a prominent Somali elder, a Professional Accountant, a widely respected Businessman, and a Human Rights Activist among the Somali community in Kenya during the British colonial administration. Hailing from the Geri Kombe (Sheikh Yussuf Mama-Abayoonis) clan of the broader Darod Somali family, Ahmed was almost sentenced to death by hanging ‘until pronounced dead’ by Kenya’s colonial administration for a crime he did not commit.

Had it not been by the intervention of the assiduous, impressive, and remarkable unity of the Somalis of that era, the old, brutally asphyxiating strangulation known as the “long drop” that was introduced in the 18th century and became a model for prisoners who were sentenced to die would have sealed his fate. Before that, shootings and beheadings were common in England with the later reserved for people belonging to the royalty.[1] Regardless, the unwarranted limitations of denying Ahmed his personal freedom on concocted charges using un-African and unjustified colonial judicial proposition did not materialize. “Hang by the neck until pronounced dead”, was a British judicial punishment coined during Britain’s domination of a quarter of the world. However, the same phrase appears in a writ of Habeas corpus 134 U.S. 160 (1890) in the State of Colorado in a petition filed by James J. Medley where the opinion of the court was delivered by Mr. Justice Miller.[2]

Unlike the French Guillotine, a machine that was introduced to chop-off the heads of those sentenced to death during the French Revolution, for colonial British Executioners, the gruesome spectacle of witnessing lifeless human heads hanging from specially designed overhead platforms was a delight they cherished. The introduction of Indirect Rule in 1934 with the admixture of imported British law created large-scale compulsion, arduous search for hegemony, the use of select ethnic groups for law enforcement, and mercenaries from other frontiers under their domain impacted colonial Nyasaland, the Gold Coast, and Kenya.[3] Working in cahoots with tribal chiefs and thousands of African askaris in khaki uniforms commanded by a few White officers allowed the colonial administrators to subjugate innocent locals.

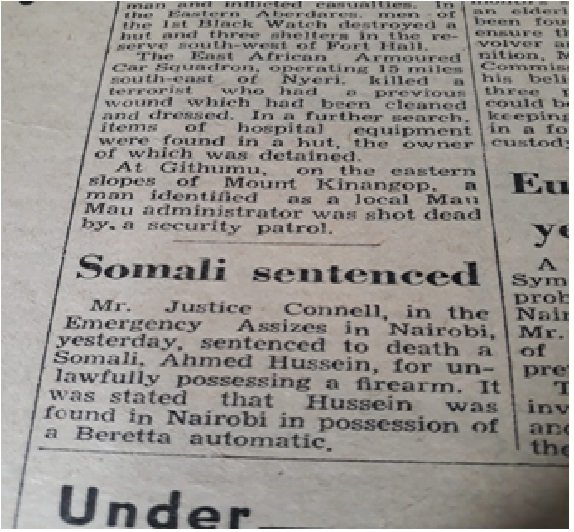

Somali Sentenced

On the sentencing day of 22nd September 1953, a Kenyan daily British newspaper carried the following agonizing report by the colonial magistrate during the sentencing:

“Mr. Justice Connell, in the Emergency Assizes in Nairobi, yesterday, sentenced to death a Somali, Ahmed Hussein, for unlawfully possessing a firearm. It was stated Hussein was found in Nairobi in possession of a Beretta automatic.”

Unfortunately, the British’s obstreperously unalloyed conduct did not materialize to push Ahmed to the gallows of death after a collective, united brilliant Somali minds forged a well-articulated plan that set him free from harm. By then, like-minded Somalis who were opposed to the unpleasantly ill-minded British occupation, regardless of clan lineage or tribal inclination, were patriotic nationalists united by a common bond to release the much-adored Ahmed from the 13 steps to the gallows. His confidants, who had long understood the precarious and irrelevant legal ramifications of the perfidious colonial court proceedings, hired a tough White Defense lawyer–a lawyer who was an Englishman according to surviving relatives of the wrongly accused Ahmed. Presumably, this acutely distressing incident happened in the early fifties when guerrilla activities across continental Africa was gaining momentum and the might of the British Empire was headed for unanticipated collapse. To the dismay of the petrified, perturbed and flabbergasted colonial administrators, Ahmed was driven across the border to Tanzania by his Somali brethren who finally waved him goodbye as he boarded a plane bound for Somalia. Ahmed did not commit any crime against the colonial government and neither was he a man known to retaliate against anyone.

Ahmed was arraigned before a White racist judge on trumped-up charges–accusations having no legal significance since the entire judicial miscalculation emanated from spies having negative agendas, according to his living son who is currently a business magnate. Without an iota of doubt, he was an innocent peace-loving man, as well as a business entrepreneur who was committed to elevating the living standards of his family and the black victims of European domination. He lived at a time when the majority of the colonized enjoyed little or no education. Despite that, Ahmed was well-educated, was multi-lingual, and well versed in Qur’anic exegesis and Islamic jurisprudence. On arriving southern Somalia, especially in the city of Kismayu, Ahmed secured employment as an accountant.

The slow-paced disintegration of Somali political inflexibility and the rise of tribal divisions started in 1963 when Britain decided not to collaborate with the Somali Republic and forsake its embassy in Nairobi, Kenya. The dysfunctionality of the Nairobi Embassy was a precursor to Britain’s prolonged commitment to side-lining the homogenous nation’s political, social, and economic integrity in all regional spheres of influence such as the Kenya-Ethiopia land disputes. This British attitude of denying Somalia a say in what mattered most to fight for the inalienable rights of its people resulted in the malfunctioning of the Somali Embassy in Nairobi. Since Somalis were treated differently and viewed from a different perspective by the colonial administration mainly for their dexterity, conviction to Islamic beliefs, bravery, and discarding alien injections that contravened their centuries-old exalted traditions and religious supremacy, the noose on their necks were always exceedingly tight and painful.

Through the application of different untried theoretical concepts of penetrating hostile territories such as the mighty Soviet Union during the Cold War, what is currently referred to as Containment Theory or the use of deterrence–theories that were proposed by pusillanimous and phantasmagorical Iconoclasts but refuted by wide-ranging scholars, researchers, and political pundits. The application of containment and deterrence did not start in modern or contemporary history. Akin to the divide-and-rule European tactics of the past, generally or individually, Somalis were treated differently either by being besieged and mortified. The refusal of Somali leaders and their loyal warriors’ absolute rejection to follow European commands and their adeptness at Islamic propagation and irredentist tendencies, crippled colonial Europe and neighboring Ethiopia’s military, ideological, and philosophical ideals to contain Somali superiority.

To the contrary, for other African ethnic groups, African exorcism practices appeared strange to the baptized British Christian whose religious beliefs dismissed satanic, superstitious, or demonic possessions. The rise of African false prophets and prophetesses forewarning the locals of the dangers of emulating imperial designs jostled the nerves of the united Kamba people–a local population bordering Somalis who were master archers. Maintaining law and order was one major problem in the occupied colonies and to curtail crime in African townships, colonial administrations were forced to put in place Native Authority Police or Tribal Messengers, though it varied from one territory to another.[4] Epidemic hysteria, psychological instability, European interpretation of African dissenters’ mindsets, and the extraordinary tactical applications of the domination of the to-be colonized in East Africa has been in the making since 1911 when the District Commissioner of Machakos, in a detailed letter, summed up the plight of the locals as possessed at the sight of the White Man.[5]

Despite the false allegations against Ahmed Hussein’s being dismissed after repeated tête-à-têtes between the Judge and the prosecutor and between the Judge and his legally eloquent lawyer, the renowned and wronged Somali Fidus Achates left a legacy to be emulated by many since the use of legal processes opened a path for many Africans who would have otherwise have been detained, prosecuted, and sentenced without legal justifications. Since the accused was not guilty beyond reasonable doubt, the prosecution, Ahmed’s legal representative, and the judge agreed on conforming to the principle of mutatis mutandis and have the case dismissed.

Adan Makina

Email:[email protected]

WardheerNews

——

Mr. Makina is the author of the upcoming book “The Political Struggles of Sultan Deghow Maalim Sambul” and a member of WardheerNews editorial board.

[1] Nagy, P. S. (1994). Hang by the Neck Until Dead: The Resurgence of Cruel and Unusual Punishment in the 1990s. Pac. LJ, 26, 85.

[2]MEDLEY, 134 U.S. 160, 10 S. Ct. 384, 33 L. Ed. 835 (1890).

[3] Deflem, M. (1994). Law enforcement in British colonial Africa: A comparative analysis of imperial policing in Nyasaland, the Gold Coast and Kenya. Police Stud.: Int’l Rev. Police Dev., 17, 45.

[4] Mahone, S. (2006). The psychology of rebellion: Colonial medical responses to dissent in British East Africa. The Journal of African History, 47(2), 241-258.

[5] Killingray, D. (1986). The maintenance of law and order in British colonial Africa. African Affairs, 85(340), 411-437.

We welcome the submission of all articles for possible publication on WardheerNews.com. WardheerNews will only consider articles sent exclusively. Please email your article today . Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of WardheerNews.

WardheerNew’s tolerance platform is engaging with diversity of opinion, political ideology and self-expression. Tolerance is a necessary ingredient for creativity and civility.Tolerance fuels tenacity and audacity.

WardheerNews waxay tixgelin gaara siinaysaa maqaaladaha sida gaarka ah loogu soo diro ee aan lagu daabicin goobo kale. Maqaalkani wuxuu ka turjumayaa aragtida Qoraaga loomana fasiran karo tan WardheerNews.

Copyright © 2024 WardheerNews, All rights reserved