By Faisal Roble

Ethiopia is described as a fragile state, if not a failed state, yet. This may or may not be the result of state decay. What is uncontested is Ethiopia is one of the leading countries worldwide for internally displaced persons (IDPs) since World War II, hosting more than 4.3 million IDPs who lost their homes and livelihood; between 600, 000 and over one million people estimated to have been killed in the two-year bloody that started in the region Tigray region 2020 and spread to Amhara and Afar regions before the guns were finally silenced in November 2022.

The Tigray war is unlike anything the world has witnessed in recent history. It was marked by war crimes and crimes against humanity such as mass rape and other forms of sexual assault including sexual slavery, starvation used as a weapon of war, extrajudicial killings of civilians and most of all a de facto siege in the Tigray region, home to at at least six million Ethiopians. It is this brutal nature of the war that makes the argument valid that the Ethiopian state has indeed decayed.

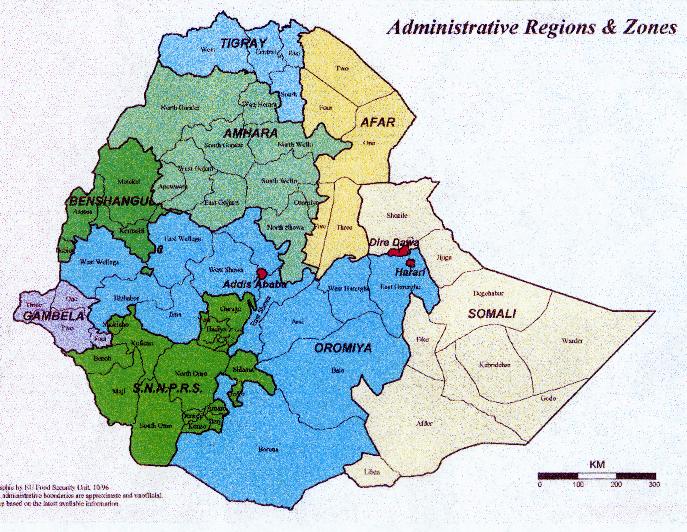

This piece will describe the causes for state decay and major national groups in the country that are locked in a virtual political disentanglement. In the past, most of the conflicts originated from regions casually known as ‘the periphery.’ However, the war theaters in the current devastating conflicts are centered around Ethiopia’s core regions, especially Oromia and Amhara regions, undermining the traditional concepts of state authority and legitimacy.

Further towards the second half of this piece, how Ethiopia’s decades-old state-building process thus far pursued the antidemocratic approach, which failed to address the demands of the Somalis, the third largest national group in Ethiopia, but one of the regions described as being Ethiopia’s quintessential ‘periphery’.

State decay at the center

With its multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multi-religious population hovering around an estimated 120 million and inching towards 160 million by 2040 according to some projections, Ethiopia is a country with a unique history and geography.

With its story of “The Battle of Adwa”, the story of triumph by a black nation over the invading colonial power of a western country, Italy, Ethiopia as a country claim to be the source of pride for many African nations. And yet it is also a country that historically enslaved and/or internally colonized its own peoples. It is this duality about Ethiopia that perpetually makes the state formation argument a contested space.

There is a pax Ethiopiana narrative favored by the centrists versus a narrative by proponents of the right for self-determination of nations. The 1974 Derg revolution and the 1975 proclamation of land ownership reform, a revolutionary law that handed about 10 billion hectares of arable land back to smallholders who are mostly in the southern and eastern parts of the country dealt the first blow at the center’s grip over power. (The Derg revolution is 50 years old as of this April). Second, the passage of the 1995 Ethiopian Federal Constitution, which legally rearranged power by designating about nine autonomous regional power geographies, sealed a major portion of rights demanded by different national groups

There are three more interrelated contemporary factors that are challenging state-building in Ethiopia. One is the question of nations and nationalities, which is the result of the hegemonic political culture Abyssinians imposed on a decidedly defiant periphery region. Somalis continued to be the most defiant national group against this imposition by the center.

The second is the 2020-2022 Tigray war, which dealt further divide between the Amhara and Tigrayan communities, two national groups representing differing views of state-building in Ethiopia but had peaceful co-existence as neighboring regions even in post 1991 state formation.

Although Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed presided over the war that pitted these two regions, Amhara Special forces, local militia and the non-state armed group ‘Fano’ supported by Amhara elite both inside and outside the country, have been the culprit in what is now recognized as the single deadliest war since World War II. The long lasting outcome of this is its potential contribution to an ever-more assertive Tigray as a ‘periphery.’

The third factor is the ever-decaying center itself that refused to democratize state structure, thus displaying its inability to peacefully hold the center and the periphery together except by brute force. Therefore, the lethal combination of a freer and assertive periphery and a progressively decaying center have weakened the hitherto state-sponsored pax Ethiopiana position. With credible and legitimate concerns, even the Amhara peasants are now feeling betrayed by the center as we are witnessing the Fano defiance against Addis Abeba.

In addition to the demise of the aristocracy and a tightly knit bureaucracy, the other contributing factors to the ever-decaying state power at the center are the recent divisions within the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church (EOTC), and a dwindling foreign military support and diplomatic alliance with the center from Ethiopia’s traditional allies.

For example, the acceptance of the concept of nationality-based federalism by Ethiopia’s traditional allies in the West, the breakdown of Amhara-Tigray alliance, the proliferation of the Pentecostal

Churches that are siphoning congregation members from the Orthodox Church, rapid urbanization in highland Ethiopia, a dwindling surplus transferred from the south, and institutionalization of regional governments in the last thirty years have collectively contributed to the making of deep and possibly irreparable cracks in the center.

Although Christopher Clapham still hangs on to the traditional way of explaining dangers to Ethiopia as originating from the “pastoralist zone” such as “Somalis, Borana, Oromo, Sidama, and Afar” he fails to address that the contemporary armed triangle in the African continent is the axis of Amhara-Tigray Eritrea.

Driven by both old and new identity politics, thousands of heavily armed militias are facing each other on the shared borders between three groups. As a matter of fact, northern Ethiopia is today divided militarily, politically and socially, all of which typify the attributes of the decaying Abyssinian center.

None other than the 22 June 2019 high level assassination of Amhara state president and other high level officials, which was engineered by a rising Amhara nationalist, Brigadier General Asamenew Tsige, indicates the crescendo of the decaying center. The International Crisis Group wrote “the 22 June assassinations and alleged attempted regional coup came as a stark illustration of the gravity of the crisis affecting both the ruling party and the country.”

Victims of the attempted coup included Amhara’s state president, Ambachew Mekonnen, who was a close ally of Prime Minister Abiy, as well as Migbaru Kebede, the Attorney General of Amhara regional state, and Azeze Wasse, the regional administration’s public organization advisor. In Addis Abeba, General Seare Mekonnen, Chief of staff of the national defense forces who was a Tigrayan, and Major General Gezai Abera, a retired general visiting Seare were killed the same night.

Prior to these assassinations, Asamenew was riling up his followers in their thousands with the rhetoric to turn the clock back to the political culture of imperial Ethiopia. Three years later following said foiled coup, Amhara region is the most unstable region where a bloody war between Amhara militia and the Ethiopian National Defense Forces is causing havoc on civilian lives and their livelihood.

Over the spoils of the decaying state are three forces competing to shape Ethiopian political narrative. The first group calls for a central government that seeks to remove Article 39 that guaranteed the right of nations and nationalities for self-determination from the 1995 FDRE Constitution. For example, Asamenew and the followers of his ideological conviction, the political party formerly known as Ginbot 7, which today became Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice (EzEMA), the opposition National Movement of Amhara (NaMA) and a host of other collectives under the various Fano forces, as well as a group of other registered political parties operating in Ethiopia are at the forefront of advocating for this cause. This group on Ethiopia’s political right believes that Ethiopia’s multi-national federalism is the root cause of the crises the country is facing today and will eventually lead to disintegration.

The other group, from the newly formed opposition political party Sidama Federalist Party (SFP), to the oldest ones Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), as well as armed groups such as the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), Gambella Liberation Front (GLF), are struggling not only to preserve the status quo as per the 1995 constitution, where autonomy for regions was hitherto nominal while disproportionate power remains in the center, but also for more devolution of power from the center.

Such has been the scenario during the 27 years of EPRDF rule that mainly catered to the four dominant ruling parties of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO), Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM), and Southern Ethiopia People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM). As the ruling party along with five other satellite parties from Ethiopia’s ‘periphery’ this group claimed to defend the 1995 FDRE Constitution, but it was more rhetorical than practical.

Since Prime Minister Abiy came to office in April 2018, the ruling Oromo political elite have moved towards the Ethiopian right’s worldview. Albeit short lived, the popular political alliance called Oromara, standing for Oromo-Amhara preceded, and in many ways, facilitated Abiy’s ascent to power. But the establishment of Prosperity Party (PP) by Abiy Ahmed was the first death knell for any possibilities of a meaningful political purpose of this alliance, which had already kicked off by alienating the TPLF, or was formed for the sole purpose of it. With no clear long-term strategy except being anti- TPLF, this alliance is now undergoing a violent divorce in the immediate wake of the Pretoria peace agreement, and the re-emergence of federalist rebel groups including the OLA. The armed violence between the federal forces and the Fano militia that has gripped Amhara region for the last 5-6 months is the physical manifestation of this divorce.

The third group largely comes from hitherto colonized peoples the ‘periphery’ such as the Somalis, Afaris, and the Sidama, among dozens of other nations, whose core beliefs in the right to self determination is sacrosanct, and seem to settle for either complete independence or a functioning multinational democratic federal system. If there is any position these disparate groups share, it is the belief that Ethiopia could disintegrate if an inclusive and equitable political solution is not found.

Different experts and scholars examined or opined the delicate nature of the contemporary Ethiopian state. Herman Cohen, former Undersecretary for African Affairs commented in a tweet dated 24 June 2019 following the multiple assassinations stated that it was “an attempt by ethnic nationalists to restore Amhara hegemony over all of Ethiopia that existed for several centuries prior to 1991. That dream is now permanently dead.”

Only days before the coup, Ambassador Johnnie Carson of the United States Institute for Peace (USIP) warned of the potential fragmentation of Ethiopia. In a high-level conference dubbed “A Changing Ethiopia: Lessons from the US Diplomatic Engagement,” the last serving four US ambassadors assigned to that country (1991 through 2006) shared their constructive insights about the decaying polity of that country. The diplomats all agreed that unless a concrete democratization process, including free and fair elections, replaced the stubborn political culture, there were potential factors that could lead to the country’s fragmentation.

Ambassador Carson, who in the past served as the United States Undersecretary for Africa Affairs during President Obama’s administration, and is a long-time career diplomat, delivered impactful introductory remarks assessing the changes that were taking place in Ethiopia. Without mincing his words, he loudly expressed his fear of a potential fragmentation of Ethiopia and likened such a possibility to the former Yugoslavian experience. For Carson to openly raise stakes so high in public and pronounce the possible fragmentation of Ethiopia was but a serious warning. The fact that the litany of promising reforms that Ambassador Carson and the remaining participants credited Abiy for initiated have all since gone south adds up to the warning.

The latest rise and subsequent revolt of the Amhara Fano in the summer of 2023 against the very administration that the region relies on in its power-relation with the center raises the spectrum for a possible fragmentation of Africa’s only home-grown empire. And it remains so.

Read the full article: State Decay: The case of Ethiopia and the Somali demand for self-determination

Faisal A. Roble

Email: [email protected]

———-

Faisal Roble, the former editor of WardheerNews portal is Principal City Planner and CEO for Racial Justice & Equity for the Planning Department, Los Angeles City.

—————-

Related articles:

1.Repercussions of acrimony: Al shabaab receives new year’s gift from Ethiopia By Adam Aw Hirsi

2.Ethiopia-Somaliland deal: A threat to Somalia and regional stability in the horn of Africa By Ahmed I.

3.Into the abyss: Somalia to become the century’s Armageddon theatre By Adan Ismail

4.Somalia triumphs in diplomacy: Safeguarding sovereignty By Aydarus Ahmed

5. Countering the dangerous ideology of PM Abiy Ahmed By A Baadiyow

6. Somalia must reconsider its policy towards Somaliland amidst the Ethio-Somaliland MoU By M.Rage

7 .What will become of Abiy Ahmed’s ‘acts of aggression’ against the Somali people? By Dr Aweys O.

8. A pact cast adrift: Navigating the legal maelstrom of the Ethio-Somaliland accord By Dayib Sh. Ahmed

9. The escalating Ethiopia-Somalia rift: A precarious path to conflict By Hassan Tahir

10. Has Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed failed history at the school? failure in history may lead him to failure in leadership By Prof Abdisalam M Issa-Salwe and Abdullahi Salah Osman

11. Abiy Ahmed’s MoU with Muse Bihi threatens Horn of Africa stability By Abdirahman Baadiyow

12-Calculated ambiguity: A sovereign port, access to the sea or a naval base? By Prof Ezekiel Gebissa

13-The historical search for a sea outlet and leadership legacy By Faisal A Roble

14 .Ethiopia and Somaliland deal: A declaration of war against Somalia By Hassan Zaylai

We welcome the submission of all articles for possible publication on WardheerNews.com. WardheerNews will only consider articles sent exclusively. Please email your article today . Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of WardheerNews.

WardheerNew’s tolerance platform is engaging with diversity of opinion, political ideology and self-expression. Tolerance is a necessary ingredient for creativity and civility.Tolerance fuels tenacity and audacity.

WardheerNews waxay tixgelin gaara siinaysaa maqaaladaha sida gaarka ah loogu soo diro ee aan lagu daabicin goobo kale. Maqaalkani wuxuu ka turjumayaa aragtida Qoraaga loomana fasiran karo tan WardheerNews.

Copyright © 2024 WardheerNews, All rights reserved