By Oliver Mathenge The Star

Somalia bypassed the AU, Igad and the EAC for a Eurocentric arbiter long discarded by major powers — the ICJ

UN members appreciate that only when states are unable to resolve their dispute peacefully can they then submit it to tribunal ITLOS, court ICJ or any other arbitral body.

When Somalia filed a maritime boundary dispute at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2014, it drove a wedge between two countries whose relationship is like that of Siamese twins.

Kenya has long been a protector and defender of Somalian interests, yet it now found itself at loggerheads with its northeastern neighbour.

To date, theories are awash as to what really prompted Somalia to take Kenya to the ICJ at The Hague, yet there are so many systems of dispute resolution in Africa.

Perhaps only historians will tell when they analyse the various cases. That notwithstanding, was the ICJ the only option for Somalia? In the recent past, theories have been posited of the possible decline of the ICJ, the judicial organ of the United Nations and the preeminent international court.

On one hand, there have been allegations on the impartial application of the law by the judges on the pretext of serving national interests. On the other hand are claims that the court has been a victim of conflicting interests among member states, who use and control it.

While African states have in the past rushed to the ICJ and the Permanent Court of Arbitration to resolve territorial or boundary disputes, concerns persist on the partiality of these judicial bodies.

There have been accusations that the courts apply Eurocentric international law that compromises the interests of African countries. Further, there are concerns that the composition and staffing of these courts remain unrepresentative of Africa.

Perhaps only historians will tell when they analyse the various cases. That notwithstanding, was the ICJ the only option for Somalia? In the recent past, theories have been posited of the possible decline of the ICJ, the judicial organ of the United Nations and the preeminent international court.

On one hand, there have been allegations on the impartial application of the law by the judges on the pretext of serving national interests. On the other hand are claims that the court has been a victim of conflicting interests among member states, who use and control it.

While African states have in the past rushed to the ICJ and the Permanent Court of Arbitration to resolve territorial or boundary disputes, concerns persist on the partiality of these judicial bodies.

There have been accusations that the courts apply Eurocentric international law that compromises the interests of African countries. Further, there are concerns that the composition and staffing of these courts remain unrepresentative of Africa.

UNCLOS, ICJ AND THE RELUCTANCE OF STATE PARTIES

Chapter 1 of the Constitution of Kenya, 2010, recognises the supremacy of the Constitution, confirming that the Constitution is not subject to challenge by or before any court. It affirms that the general rules of international law form part of the laws of Kenya and recognises that any treaty or convention ratified by Kenya forms part of the laws of Kenya.

Why, then, the debacle with Somalia?

On June 11, 2009, the Secretariat of the United Nations registered a Memorandum of Understanding between Somalia and Kenya to Grant to Each Other No-Objection in Respect of Submissions on the Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf beyond 200 Nautical Miles to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.

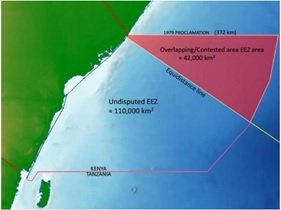

The MoU, registered under registration number I-46230, recognised there existed a “maritime dispute” between the two coastal states, whose extent covered an overlapping area of the continental shelf. It noted further that despite the two states having differing interests on the area under dispute, they remained determined to work together to safeguard and promote their common interest with respect to the establishment of the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

The Transitional Federal Government of Somalia indicated at the time of the signing of the MoU that it would submit to the United Nations Secretary-General preliminary information indicative of its intention to proclaim the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

This, it stated in the MoU, was solely to comply with the time limits stipulated in Annex II of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). Article 4 of Annex II indicates that where a coastal state intends to establish the outer limits of its continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, it must submit to the Commission supporting scientific and technical data within 10 years of the entry into force of the Convention for that particular state.

The Law of the Seas Convention (LOSC) was entered into force for Somalia on November 16, 1994, and on July 21, 2014, the Federal Government of Somalia submitted to the CLCS information on the limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

During the signing of the MoU, Somalia stated that its position would not in any way prejudice the positions of the two coastal States with respect to the maritime dispute between them; nor would it prejudice the future delimitation of maritime boundaries in the area under dispute, including the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

The Government of Kenya on its part did not object to the inclusion of the areas under dispute in the submission by the Somali Republic.

Further, the two states, according to the MoU, agreed to make separate submissions to the CLCS, requesting the Commission to make recommendations with respect to the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles without regard to the delimitation of maritime boundaries between them.

In fact, the two states gave their consent to the consideration by the Commission of their submissions in the area under dispute. They further agreed that the submissions made before the Commission and the recommendations approved by the Commission would not prejudice the positions of the two countries with respect to the maritime dispute between them; nor would it be prejudicial to the future delimitation of maritime boundaries in the area under dispute.

The MoU, which entered into force on June 7, 2009, registered that the delimitation of maritime boundaries in the areas under dispute, including the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, would be agreed between the two countries on the basis of international law.

This would be after the Commission had concluded its examination of the separate submissions made by each of the states, and made its recommendations to the two concerning the establishment of the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

What, then, prompted Somalia to act in the manner it did against Kenya?

Read more: Inside Somalia’s Indian Ocean border claim, and why Kenya disputes it

Source: The Star

Leave a Reply