By Paul Kirby

Geert Wilders doesn’t like being called far-right; he insists he’s just speaking up for ordinary people.

But it was only by putting some of more inflammatory policies on hold and dialling down his hardline rhetoric that he was able to broaden his appeal and secure election victory.

When he burst into Dutch national politics 25 years ago, he was nicknamed Mozart for his sweeping mane of blonde hair. His hair has greyed but his powers of communication are at their peak.

He regularly outperformed his rivals with slick, bite-sized slogans on asylum and immigration during the almost nightly TV debates in the run-up to the vote.

“The Netherlands can’t take it anymore,” he said. “We have to think about our own people first now. Borders closed. Zero asylum-seekers.”

Ask him if he is far-right, and he will deny it.

“We are a country of consensus-building. We don’t even have that many far-right people in our country; we never will,” he told the BBC. “Indigenous people are being ignored because of the mass immigration… they feel mistreated.”

To make his party more palatable to mainstream voters, he declared that his party’s manifesto plans to ban the Koran, Islamic schools and mosques was going in the koelkast – the fridge.

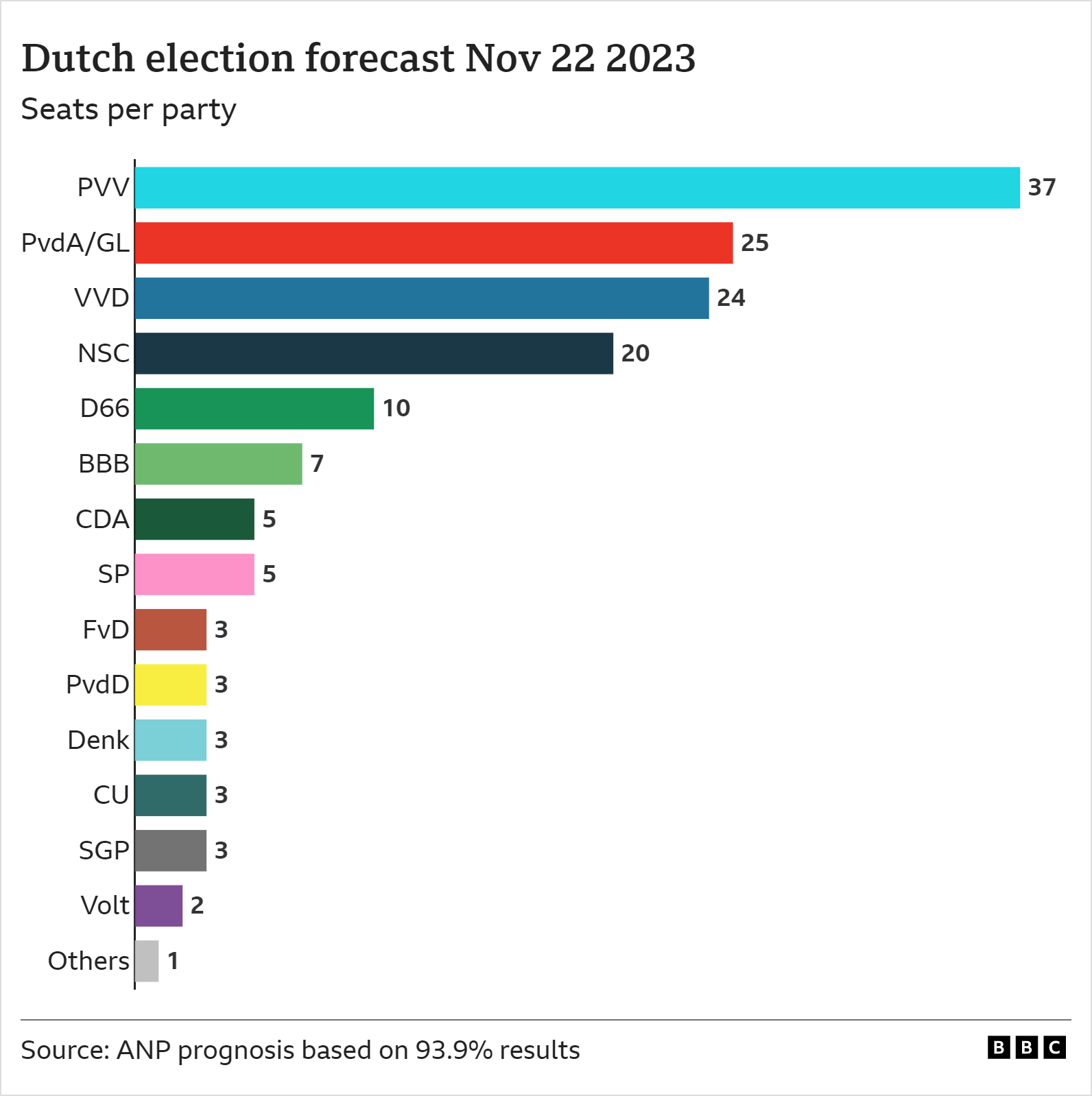

This apparent signal of moderation helped his party to more than double its representation in parliament, from 17 to 37 seats.

The PVV victory is viewed with trepidation by some in the Netherlands’ Muslim community, who fear a difficult period ahead.

“For Muslims, our sense of security is no longer secure,” Muhsin Koktas, head of the Contact Body for Muslims and Government, told Dutch TV.

Mr Wilders’ policies, including a proposed ban on Islamic headscarves in public buildings, are still in black and white in his party manifesto.

And he has been in trouble with the courts for years for his verbal attacks on immigrants of Moroccan origin.

Geert Wilders has regularly appeared in court for incendiary remarks about Moroccans

He was convicted of insulting people of Moroccan descent for leading a chant at a 2014 rally demanding “fewer” Moroccans, but eventually cleared of incitement.

During the 2017 election campaign, he called some Dutch Moroccans “scum”.

Mr Wilders embodies the Freedom party for most Dutch people, but in reality its ideology has been steered by his right-hand man Martin Bosma, who has been with him from the start.

Mr Bosma was seen celebrating with a little dance on Wednesday night.

Sometimes called the Dutch Donald Trump, Mr Wilders hailed the 2016 US presidential elections as Americans taking their country back. After Wednesday night’s victory, he proclaimed that he would “put the Dutch back as number one”.

The Freedom party leader has railed against “the political elite in The Hague and Brussels” for much of this century, even if he himself has become as much part of the establishment as any other Dutch MP.

Mr Wilders may be a firebrand and a radical, but he is affable and privately gets on well with many of his rivals.

And he has had 24-hour security for close to 20 years because of threats to his life. He once said he could no longer imagine what it was like to walk along a street by himself.

He has been married for 30 years to Krisztina, a former Hungarian diplomat.

Although much of his career has been spent in opposition, he did prop up Mark Rutte’s first centre-right government for more than a year and a half, and then triggered its downfall in 2012.

His maverick, straight-talking nature appeals to a significant section of Dutch society. Earlier this year it was a farmers’ party led by another straight-talking leader, Caroline van der Plas, that won provincial elections.

Almost a third of her voters defected to Mr Wilders on Wednesday, although her BBB party’s seven seats could be useful towards forming a coalition.

Mr Wilders’ anti-EU message has been consistent ever since he helped derail the EU’s bid to create a constitution in 2005, when the Dutch and the French turned it down in two referendums.

He still wants to leave the EU, but recognises most Dutch voters don’t. He will still push for a referendum on “Nexit”, even if he is unlikely to convince prospective coalition partners to agree to it.

Dutch coalition negotiations can last months. Forming a majority with centrist parties will probably require him to drop the most radical elements of his party platform.

Mr Wilders wants strict limits on immigration and a complete halt to all grants of asylum in the Netherlands, proposals he may have to moderate in coalition talks.

He also wants to “push back” asylum seekers seeking to enter the Netherlands from EU neighbours and to deport those found guilty of criminal offences.

Other ideas, such introducing work permits for EU nationals would be challenged in the European Court of Justice and again would be unlikely to get beyond more centrist parties. But he may find support for significantly reducing the number of international students in the Netherlands.

His closest allies in the EU are on the nationalist right.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, French far-right politician Marine Le Pen, and Vox leader Santiago Abascal have all welcomed his victory.

But his success is not dissimilar to Giorgia Meloni’s election victory a year ago in Italy. She too moderated some her most radical policies and reaped the reward at the ballot box,.

She went on to form a right-wing coalition. It is far too early to say whether Geert Wilders can do the same.

Source: BBC

Leave a Reply