By Faisal Roble

Existential Politics of Ethiopia

The most unsettling diplomatic issue about Ethiopia in the affairs of the Horn of Africa region is its size, history of conflicts, and its status as the only country that starves for a sea outlet. Owing to a political collaboration between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), Eritrea succeeded to secede from Ethiopia in 1993, thus rendering it a landlocked ancient empire. And such a new development also eroded Ethiopia’s hegemonic status in the region.

Prior to that, Ethiopia owned two well-developed ports on the Red Sea – Musawa and Assab. Both are today part of the newly established state of Eritrea. Whereas three of the four HoA countries (Somalia, Djibouti, and Eritrea) are blessed with sizeable shorelines, Ethiopia is landlocked with its 104 million population that which will grow to about 170 million by 2040. Unlike the other three countries, Ethiopia sees its search for a gateway to the sea as an existential policy.

With its 3,333 km coastal line, extending from the edge of the Red Sea on the border of Djibouti to the Indian Ocean, Somalia’s well-endowed with a rich oceanic resources. This endowment is least utilized because of political instability in Somalia, and it is becoming appetizingly more attractive to this starving beast of the region – Ethiopia – that sits in the belly of the region. Both Eritrea with its 2,234 km and Djibouti with 314 km coastal lines stand in the way of Ethiopia’s access to the Red Sea waters.

On its part, Ethiopia expressed serious concern to remain oblivious to the rich coastal resources in its backyard, while forces from afar take advantage of mainly Somalia’s coast lines, argued Ethiopia’s commander of the army. Through diplomacy or otherwise, Ethiopia is determined to have access to some of these warm waters. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed recently said on state TV this: “We built one of the strongest ground and air force in Africa… we should build our naval force capacity in the future.” The PM will come up soon with a concrete plan to implement this vision. As a first step, Ethiopia has purchased about eight military and commercial fleets from France, and soon these arsenals will be ready for delivery. Many observers of the region believe that these ships are slated to be docked either in Somalia or Djibouti lest Eritrea already made its position clear in that Ethiopian ships will not bel docked in her ports.

Given the challenging and incongruent political and historical landscape that characterize Ethiopia, forging ahead with the Abiy-proposed HoA integration could prove problematic. As we have seen in part I of this essay, the historical, political, social, and poverty issues that are layered in this region make regional integration less permissible. If so, why rush to a legally binding regional integration whose time is not here? What is in it for Somalia, knowing the mess in which Somalia is? What are the safeguards put in place to protect Somalia from an avalanche of a north-south population shift that is in the air? What is the alternative to the Ethiopian sponsored HoA integration so that the region can openly trade with the least negative impact on each other?

In the eyes of many Somalis, Ethiopia is deriving the HoA regional integration proposal for two simple reasons: securing access to Somalia’s underutilized ports. In his book “Ethiopia at Bay: A Personal Account of the Haile Selassie Years, 1974,” John Spencer, who served as Emperor Haile Selassie’s longtime advisor, in detail wrote on Ethiopia’s claim over Zayla. To that end, Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam’s administration showed serious interest in using Zayla as Ethiopia’s outlet and consequently conducted a Zayla-corridor fiscal assessment and feasibility study (This feasibility study is different from the current Jigjiga-Berbara corridor which the Dubai-based DP World funded).

Ethiopia’s Objectives

Forty-five years after John Spencer wrote his evaluative book pertaining to Ethiopia sea outlet options, this time Ethiopia wants to get to it objective through a diplomatic [constructive engagement] means, the centerpiece of which is the HoA integration proposed by PM Abiy. If Ethiopia considered Somalia in the past a security threat to its strategic interests, the current reality on the ground encourages Ethiopia to treat Somalia as its sphere of influence while invoking the concept of integration being used as the tool that get the job done. In other words, having an integrative relationship with Somalia is a policy option so far Ethiopia finds not only possible but lucrative and advantageous to its national and strategic interest.

The second objective which is born out of Somalia’s collapsed state is to give Ethiopia a venue to unburden its massive population growth. Somalia’s landscape and its low population density represents (1) an opportunity for Ethiopians to migrate and earn living by doing menial jobs and still earn better living wage than they do inside Ethiopia; (2) a venue to settle a portion of Ethiopian population in Somalia. The combined outcome from these two objectives for Ethiopian leaders is not only attractive but an existential reality. And that is why PM Abiy pushes the untimely integration with Somalia.

Ethiopia has colonized a large swath of Somali-inhabited area for over 150 years. Somalia and Ethiopia fought two wars (1964 and 1977) over the rights and self-determination of Somalis that Emperor Menelik incorporated into the Ethiopian empire through a violent conquest. Ethiopia also swallowed Eritrea in the 1950s by reneging on a mutually agreed federation. Since that time, the two sides have been at war with each other until 1993 when Eritrea received its independence from Ethiopia. Many Somalis view the proposed HoA integration with a similar suspicion and fear that Ethiopia may attempt to swallow Somalia or parts of Somalia. Such a suspicion fans the fear of an Ethiopia-led HoA integration.

Both Ethiopia and Eritrea have clear objectives from the proposed integration. Eritrea used or continues to use it as a tool to (1) come out from a 300year isolation, (2) neutralize Ethiopia by infiltrating the political and economic life of different disgruntled groups, (3) neutralize its sworn enemy of TPLF; (4) ensure that Ethiopia does not become the center for an Eritrean Spring to oust Isaias Afworke, who came to power with the help of the late Meles Zenawi; and (5) marginalize Djibouti economically and make Ethiopia more dependent on Assab.

For Ethiopia, the objectives are much salient: it simply wants to make its generational dream come true – have unabated access to Somalia’s warm waters both for commercial and military uses. By doing so, it could easily undermine the dreams of those who have always challenged the existence of Ethiopia and minimize its security threats from the east. In a fascinating 1978 article, Nurrudin Farah canvases Ethiopia’s unyielding search to find which way leads to a successful journey to Somalia’s warm water. That journey seems to materialize through the HoA integration scheme.

Somalia’s Objective

By all accounts, Somalia has yet to come up with a coherent theory of why it wants to open up its sea ports to its erstwhile enemy at this juncture. At least as expressed by its leaders, Somalia’s evolving theory maintains that integration with Ethiopia will open new markets for Somali traders. Another implicit theory is that such a relationship with her strong neighbor will also help Mohammed A. Farmajo consolidate Villa Somalia’s power and undermine his rivals in the Somalia Theater – limiting the movement of Somali regional presidents and eliminate any chances for international recognition for Somaliland’s unilateral secession lest Ethiopia’s role is indispensable.

As far as the second theory is concerned, that has already been shattered into tatters since Ethiopia has upgraded its diplomatic relationship with Somaliland since Dr. Abiy came to power. Here are two examples to show how Ethiopia promised to President Farmajao one thing and did quite the opposite: (1) the Ethiopian mission in Somaliland has been upgraded; and (2) what was until now a pipedream, i.e., the Jigjiga-Barbera Corridor, has been materialized without the consent of Villa Somalia. Both moves on the part of PM Abiy represent a violation of the territorial integrity of Somalia, which is to say that President Farmajo’s administration has been weakened and undermined faster than before.

From a mere business transactional point of view, Somalia, with a small GDP of 7.5% in 2018, has about 11 functioning ports. Its small size economy and the mostly mercantile-based sectors do not need all these ports. On the contrary, goes the argument advanced by HoA integrationists, Somalia needs someone else to use its ports. And that is, according to these proponents, Ethiopia because of its severe need for ports. An overview of Ethiopian economy shows that growth has been robust and at times registered an impressed 10% expansion per annum for the last 10 years, a persuasive justification and a viable candidate to utilize some of Somalia’s less utilized port. It is here where the economic argument in opening Somalia’s ports to the beast of the region makes sense and sounds rational.

The Deputy Prime Minister of Somalia called his government’s endorsement of the HoA integration as a necessary step for economic growth. At a Djibouti conference sponsored by the Heritage Institute in December 2018, he strongly argued that Somalia was not accepted to be a member of other regional (African) markets and will not turn down this offer coming from Somalia’s own backyard, i.e., Ethiopia.

Without any hard data presented, the Deputy Prime Minister of Somalia loudly lectured at a full house of Somalis that “Somali business community will immensely benefit by trading with Ethiopia and its large market.” He enthusiastically mentioned how Somalia will welcome Ethiopia’s use of Somali ports for multipurpose in exchange for providing military and political support to Villa Somalia against its forces of terrorism.

To that end, unconfirmed reports suggest that President Mohamed A. Farmajo has agreed that Mercca to be rented to Ethiopia for its use as a naval base for that country’s reestablished navy. Ethiopia has recently purchased about 8 modern warships from France and will soon need somewhere in the region to dock. Both Djibouti and Eritrea thus far made clear that they are not offering services for the reconstituted Ethiopian navy. Somalia has been silent, although on this matter, and whether Mercca is the port to dock Ethiopian fleets, no one can say for sure. The fact that the French President just finished a high profile visit to Ethiopia at the gives less comfort to many Somalis who are already suspicious of the integration that Prime Minister Abiy has been touting lately. To make matters worse, while standing on the steps of Villa Somalia. PM Abiy mentioned the proposed “unification” between Somalia and Ethiopia.

Alternative to HoA integration

Whereas integration could be a positive tool to enhance trade among neighbors, the incongruent sociopolitical culture that prevails in the HOA region may prove to be an insurmountable challenge. Timing may not be on the side of proponents of this proposed integration for the dust has yet to settle in Ethiopia, especially the fallout between the government and OLF. Moreover, the Somali question in Ethiopia must be settled democratically to enhance peace and security, two prerequisites for a successful regional integration.

Africa has been toying with regional integrations for some time now. The East African Community (1967 -1977) never thrived but was stunted early in the 1970s and finally died under the weight of its own local conflicts. The oldest and still surviving African regional integration is the African Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS); it is a 15-member state organization and was established in 1975. ECOWAS was set up to foster the ideals of collective self-sufficiency for its member states. As a trading union, it was also meant to create a single, large trading bloc through ECOWAS economic cooperation.

Three decades later, ECOWAS is far from being a success story. In addition to infrastructure, tariff and custom constraints, one of the major obstacles for ECOWAS to succeed is the “role of the Nigerian leadership that often undermines the implementation of integration protocols,” because it sees herself as the global power in that region. In short, politics is the major impediment for ECOWAS to successfully function. Another hindrance to African regional integration to succeed is that “majority of African “economies remain predominantly natural resource and primary commodity driven, where little value addition takes place, according to the Economic Commission for Africa Committee on Regional Cooperation and Integration (CRCI).” In the case of the HoA, a complex history complicates matters more.

Could Ethiopia with its massive population and military might dictate the terms of trade for the three HoA members as did Nigeria in the ECOWAS case? That is quite possible. And that is a serious concern to many students in the region, including this author.

Established in 1983 as the Inter-Governmental Authority on Drought and Development (IGADD), one of the oldest African regional organizations is what has morphed into the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD). This grouping brings eight countries often revered to as the expanded Horn of Africa region. Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda and Kenya and the four countries discussed here are members of IGAD. With about $319 billion of GDP, IGAD has much to offer than the Ethiopian sponsored HoA’s mere $92.6 GDP with Ethiopia controlling $80.5 billion of that GDP.

The overall objective of the IGAD grouping is to enhance security, sustainable development and regional integration.” The official text of the group reads this: “Enhancing the effectiveness of the member states’ security sector to address common transnational, regional and national security threats.”

This objective can be expanded to include trade, people’s movement, and economic development clauses and have instruments regulating all facets of integration beyond security and sustainable development. Strong and practical legal instruments promulgated as a prerequisite for integration to deal with migration is in the interest of Somalia.

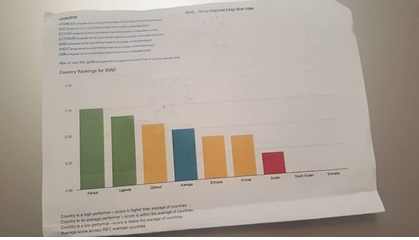

IGAD region is a much preferable option in that it is a much larger region with 230 million people and a much productive economy. As shown below, Uganda, Kenya, and Djibouti are thriving as members of IGAD. And Somalia and Ethiopia have a lot of catch up to do. In addition, IGAD is a more diversity group and it bodes well for equity. Moreover, Somali economy is fully integrated with that of Kenya. In some estimates, Somalis control over 50% of the transections taking place in Nairobi and Mombasa. Compare this to how Somalis are absent from the Ethiopian economic life and you will see that the IGAD alternative has a lot to offer to Somalis.

Conclusion

The option of the HOA integration that Ethiopia is promoting is unstable, more challenged both politically and economically. It is skewed population in favor of Ethiopia is not also in the interest of Somalia. On the contrary, the IGAD alternative is preferable for Somalia for several reasons: first, in the long run, IGAD as a region is more stable than the HoA region; second, it is a larger market and therefore provides more opportunities. Third, Somalia’s economy is more integrated with Kenya, Southern Sudan, and Uganda. Ethiopia has remained close not only to Somalia but even to Somalis inside Ethiopia and Somaliland that attempted to fairly trade with it. Fourth, the IGAD grouping may prevent the domination of Ethiopia and safeguard Somalia’s national sovereignty against its erstwhile enemy which will not hesitate to take over if opportunity presents itself. Fifth, Kenya has a better democratic culture and more modernized rules for commerce than Ethiopia; Somalia can borrow best practices from a Kenyan-led IGAD than an Ethiopian engineered HoA region, which may soon succumb to a political crisis. Lastly, Kenyan economy is twice that of Ethiopia with only half of its population.

While regional integration is good, to succeed it must have the right ingredients and come about at the right time. An expanded IGAD regional integration is preferable to an Ethiopian-engineered four-state member HOA that which is fraught by an incongruent political landscape.

Faisal Roble

Email: faisalroble19@gmail.com

———–

Faisal Roble, a writer, political analyst and a former Editor-in-Chief of WardheerNews, is mainly interested in the Horn of Africa region. He is currently the Principal Planner for the City of Los Angeles in charge of Master Planning, Economic Development and Project Implementation Division.

-Part I- Challenges to Integrating the Horn of Africa Region (HOA): IGAD as an Alternative By Faisal Roble

——

References

Sihab ad-Din b in Abd al-Qader bin Salem bin Utman; translated by Paul LesterStenhouse with annotations by Richard Pankhurst, Futuh Al-Habasa: The Conquest of Abyssinia, Tsehai, 2003

Richard F. Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa, or an Exploration of Harar, London, 1896

Delebo, Labiso, Ethiopia Ye Gabar Siratina Jimir kabitalism 1900-1966 (Ethiopia’s Serfdom and infant Capitalism 1900-1966). Addis Ababa, 1983.

Eshetu Chole (Ed), Ethiopia: Rural Development Options, London, 1990

Kiflu Tadessie, the Generation: The History of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party, New Jersey, 1993

Edmond J. Keller, Revolutionary Ethiopia: From Empire to People’s Republic, Indianapolis, 1988

I.M. Lewis, Nationalism and Self Determination in the Horn of Africa, London 1983

Mohamed Afrah, Dal Dad Waayey iyo Duni Damiir Beeshay (A Land without Leaders in a World without Conscience), UK, 2002

Bereket Habte Selassie, Riding the Whirlwind: An Ethiopian Story of Love and Revolution, New Jersey, 1993

John W. Herbeson, “The Ethiopian Crisis: Alternative Scenarios for Change,” Horn of Africa Journal, Vol XIV, Number 1&2, 1991

Faisal Roble, “Conquest, Conflict, and Collective Punishment: Identifying Stakeholders in the Somali Ogaden Region,” Horn of Africa Journal, Vol XXIX, New Jersey, 2011

Amare Tekle, “Military Rule in Ethiopia (1974-87): The Balance Sheet, Horn of Africa Journal, Vol XIV, No. 1&2, New Jersey, 1991

Leave a Reply