By Aweys Omar Mohamoud, PhD

In this article, we look at the coup d’état of 1969 whose regime lasted for over two decades, until January 1991. Read also part 1 of the brief historical reflections.The other topics to be covered in this series include ideas for reconciliation, and the need for a new leadership with great vision in 2021.

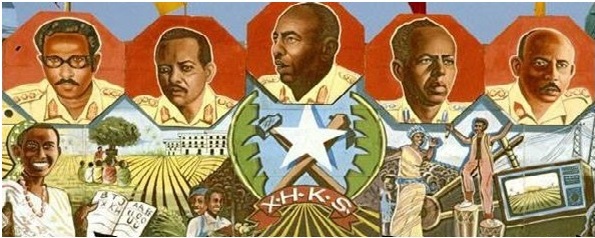

In the early hours of 21st October 1969,[1] just before the formal election of a new president, a group of army officers staged a bloodless coup d’état. It was claimed that Salad Gabyre Kediye and the police chief Jama Qoorsheel were the coup leaders alongside Siyad Barre, the existing army Commander. Significant political figures were detained, the constitution suspended, the Supreme Court abolished, the National Assembly closed, and political parties banned. The country was henceforth renamed the Somali Democratic Republic to be ruled by a Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC), under the chairmanship of General Siyad Barre.

Shortly after, a power struggle was said to have ensued inside the SRC’s leadership. In 1971, Gen. Salad Gabeyre Kediye, who was officially holding the title of “the Father of the Revolution”, and then Vice President Mohamed Ainanshe were charged with attempting to assassinate President Siyad Barre. Both men were shortly afterwards found guilty of treason and, along with Colonel Abdulkadir Dheyl, were publicly executed.[2]

Coup d’état is a French expression which means a ‘sudden blow of state’ and dates back to 17th century France. The Encyclopaedia Britannica defines it as the sudden, violent overthrow of an existing government by a small group of persons. A slightly different definition is provided by E. N. Luttwak in his classic work, Coup d’état: a practical handbook: ‘a coup consists of the infiltration of a small but critical segment of the state apparatus, which is then used to displace the government from its control of the remainder.’[3]

Some of the most cruel and venal dictators in the world have taken power via a coup. In the 1960s and 1970s coups were a regular occurrence in Africa. Naunihal Singh who studied the strategic logic of coups that took place between 1950 and 2000 suggests that 80% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa and 76% of those in North Africa and the Middle East had at least one coup attempt during this period.[4]

A coup is different from a revolution. The latter is usually brought about by uncoordinated popular masses, with the aim of changing the social and political structures of society, as well as the personalities in the leadership. By sheer craftiness, the plotters of the coup d’état of 1969 used the term revolution for their putsch. The implication of their claim was that it was “the people” rather than a few plotters who overthrew the government and assumed the authority of the state. Thus, the obscure aims of General Siyad Barre were labelled as the “principles of the Supreme Revolutionary Council”.

E. N. Luttwak contends that corruption is the trigger of many a coup d’état. In the absence of significant corruption, the coup plotters who risk their necks to overthrow elected leaders and seize control of the government can gain only an increase in status, but not vast wealth. The difference in salaries and pensions between colonels and presidents is downright negligible as compared to the risks. With corruption, however, those who seize power can enrich themselves enormously, sometimes by simply taking what they want from the country’s national bank with its foreign-exchange reserves, or, more discreetly, by taking their cut on all state purchases, by exacting bribes from all who need anything from the government, by securing loans from state banks that are never repaid, or by setting up relatives and even family members as business agents.[5] State collapse in Somalia was not a short-term phenomenon but a cumulative, incremental process similar to a degenerative disease, and it began with these corrupt practices of the late dictator’s regime.

Luttwak proposes three preconditions for a coup d’état to succeed.[6] The first precondition is that the social and economic conditions of the country must be such as to confine political participation to a small fraction of the population. The second precondition is that the state must be substantially independent, and the influence of foreign powers in its internal political life must be relatively limited. For instance, a coup is not worth attempting if a Great Power has significant military forces in the country concerned. The third precondition of a coup is that the political power of the state should be concentrated in one controlling center for the nation as a whole. The essence of a coup is the seizure of power within the main decision-making center of the state and, through this, the acquisition of control over the nation as a whole. But if there are several political centers, such as the existence of regional entities or FMSs (as our current constitution provides for) whereby the structure of leadership is too firm and intimate with the people, it would be impossible for a coup to take place. The lesson to learn from here is that if there were strong FMSs in 1969,[7] there would not have been a coup d’état led by Siyad Barre and Co., think of the millions of lives that could have been saved, not to mention all the nation-building implications sixty years of political stability would have had for the entire Somali peninsula.

The new regime claimed that it was going to ‘eliminate corruption and tribal nepotism’ and create a ‘just and honourable society in which proper attention would be given to real economic and social betterment for all’.[8] General Siyad Barre also introduced what he called ‘Scientific Socialism’ (‘Scientific Siyadism’ was a term aptly coined by I M Lewis) which principally meant the ‘nationalization of manufacturing and service industries.’ Despite these proclamations, Siyad Barre himself covertly relied on ‘old and time-honoured ties of clan loyalty.’ He had constructed his inner power circle of members of his own Marehan clan and other loyal clans. Much later, as his credibility diminished and paranoia increased, he has increasingly surrounded himself with members of his immediate family, i.e. his sons, daughters and in-laws.[9]

In Siyad Barre’s Somalia, ‘Scientific Socialism’ had become an ‘industry for controlling power’ and using violence and corruption through the state apparatus in various guises, including bribery, tax exemptions, neglect, intimidation, and outright violence. He was a dictator sparing no effort to pull out all the stops in the traditional ‘clan political system’ to secure his survival, to seek the loyalty of other clans, and to pit one clan against another clan to destroy his enemies.[10] Needless to say, Siyad Barre’s attempts to reorder the mosaic of Somalia’s intricate social structure by weakening kin and clan ties have led to disastrous consequences.

With the elimination of democratic institutions, Siyad Barre brought almost the entire Somalia economy into the public sector. Under his misnomer of “Scientific Socialism”, he appropriated much of the national resources to maintain himself and a small clique from his own clan.[11] Corruption and bribery were rife in practically every department of state, office, corporation and institution in the country. As Drysdale aptly put it ‘his was an abuse of power that knew no bounds’. Corruption eats away at the foundations of trust between people and their rulers. It exemplifies the two key weaknesses of the state in the Third World: the unholy marriage of political and economic power, whereby money buys influence, and power attracts money, and the ‘softness’ of the state, to use economist Gunnar Myrdal’s term – its inability to apply and enforce its own laws so that reform, if it is legislated, rarely gets put into effect.[12]

For most of Siyad Barre’s tenor of office, there has been a serious brain-drain of competent professionals out of Somalia. There was not much of an intelligentsia left in the country and the civil service had declined correspondingly, eroded also by nepotism and corruption.[13] Health, education and other social services have also been deeply affected by the general erosion of public services. This sorry state of affairs could be traced largely, according to I M Lewis, ‘to the comprehensive politicization of all state institutions, to the upsurge of nepotism and corruption, and to a general decline in professional standards, which is one of the most corrosive and will be one of the least easily reversible legacies of Siyad Barre’s rule’.[14]

Was there anything positive that Siyad Barre did in his time? Of course, his government selected and modified the Latin alphabet as the standard orthography for the Somali language, without which there will be no literacy to speak of among the majority of the Somali people today. There was the famed rural literacy campaign of 1974, and the resulting improvements in both urban and rural literacy rates and education. But his government has also set up several cooperative farms and factories of mass production such as grain and cotton mills, and sugar cane and meat processing facilities. Another public project initiated by Siyad Barre’s government was the Shalaambood Sand-dune Stoppage. From 1971 onwards, a massive tree-planting campaign on a nationwide scale was introduced by the administration to halt the advance of thousands of acres of wind-driven sand-dunes that threatened to engulf towns, roads, and farm land.[15]

One of Siyad Barre’s most grossly negligent historical miscalculations was his authorization of the SNA’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1977, with the serious consequence of the entire communist world siding with Ethiopia against Somalia in hot war. A Russian-directed distribution of aid, weapons, and training to the Ethiopian government, which also brought around 15,000 Cuban troops to fight for the Ethiopians, ultimately pushed Somali troops out of the Ogaden in 1978. According to Greenfield,[16] there are few parallels in history where a president and his regime survive such a humiliation. A bungled coup attempt to remove Siyad Barre followed soon. But most of the coup plotters were apprehended and summarily executed, except Col. Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed (later to become President of the TFG) and several others who managed to escape abroad.

To sum up, Siyad Barre’s regime preyed on its people; denied them all or virtually all fundamental human rights and civil liberties; eschewed or made a mockery of democracy; used force to compel obedience and achieve compliance with the demands (even whims) of the dictator; obliterated the rule of law and instead followed the law of the jungle; executed opponents and took political prisoners; carried out collective punishment of families and clans; waged wars against people in various regions of the country; was often capricious in its policies and actions; totally commanded the economy; inhibited individual prosperity; was seriously corrupt; was divisive, and nepotistic; selected people not on merit, but through political patronage; built the leaders’ personality cult, and created a culture of dependency and conformity; through corruption, incompetence and bad policies, people were starving across the country while the ruler, his family and close relatives and hangers-on lived luxuriously.

On the evening of 26 January 1991, Siyad Barre was forced by popular uprising and rebellion to flee Mogadishu for his clan homeland in Gedo. He did not give up his ambition of recapturing the city for many months, and twice attempted to retake it. But in May 1991, he was finally forced into exile by General Aidiid’s fighters. He initially moved into Kenya where he was accommodated in some style at the expense of the Kenyan government. As a result of opposition groups’ protest against his presence in Nairobi, Siyad Barre and his entire party were moved to Lagos at the expense of the Nigerian President, Maj-Gen Ibrahim Babangida, who was then chairman of the Organization of African Unity. According to Greenfield, although he was treated well by the Nigerian authorities, the fallen dictator was paid scant respect by the average Nigerian, and his home was robbed more than once. Unable to the end to accept responsibility for the famine and anarchy that followed the succession struggle to remove him from power, Siyad Barre died a frustrated and embittered man in Lagos on 2nd January 1995. It is that succession struggle in post Siyad Barre Somalia that we turn to next.

Dr. Aweys Omar Mohamoud

Email: aweys6@aol.com

————————

Dr. Aweys Omar Mohamoud (@AweysOMohamoud) has a PhD from the Institute of Education, University College London (UCL). He has recently worked as an advisor to the Ministry of Education, Culture & Higher Education (MoECHE), Federal Government of Somalia in Mogadishu.

Related article

Supreme revolutionary council of Somali: Harbinger of social injustice and collapse of state-institution By Makina

Reference

[1] According to Richard Greenfield, a once prominent British political advisor to Siyad Barre, ‘the crime may not have been politically inspired, but the national assembly dithered over his successor and that is what gave the coup plotters the opportunity to bounce. See ‘Obituary: Mohamed Siad Barre’, by Richard Greenfield, Independent, Tuesday, 3 January 1995, viewed 11 July 2020, <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-mohamed-said-barre-1566452.html>.

[2] This comes from Wikipedia. Were they really executed for treason? Or was Siyad Barre drawing a line in the sand early on as to what his absolute doctrine is – that he had obtained his position by force and that he was only going to relinquish it by force as he himself has confirmed in some of his speeches, which sadly came to pass some two decades later. I have a personal anecdote to tell here. In 1976, I was a pupil at scuola media centrale in Shengani. On 15 May, the founding day of the SYL which Siyad Barre renamed as the Somali Youth Day and was celebrated, we were bussed to the Konis Stadium in A/Aziz to take part in the celebrations. We must have been couple of hundred or so children and we were paraded by our teachers in the football ground in front of the President and other dignitaries. During his speech, I distinctly remember Siyad Barre getting angry at unnamed people he was accusing of being anti-government and that they were the masters of ‘qabyaalad iyo qurun – clannism and shit’. All over sudden, he grabbed the gun from one of his body-guards standing beside him and said, words to the effect, ‘I took power by the gun – waving the gun up in the air – and will only relinquish it by the gun’. We were just kids, and I could see the anger in his face and the angry men carrying guns around him, and pointing them at us, and that really did scare me out of my wits. But Siyad Barre’s wishes were granted some 16 years later, at the beginning of 1991.

[3] Luttwak, Edward N. (2016) Coup d’état: A Practical Handbook (Revised Edition). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Allen Lane The Penguin Press.

[4] Singh, Naunihal (2014) Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups. Johns Hopkins University.

[5] Luttwak, Edward N. (2016), op. cit.

[6] Ibid., p. 46

[7] One could also surmise that if the constitutionally-mandated elections take place in Somalia before the end of this year and early next year, it would have been thanks to the FMSs not to the FGS and their leaders who are trying as hard as they can (even at this very late stage) to postpone the elections indefinitely so that they can remain in power for an extra period of time with no fixed end!

[8] Lewis, I. M. (1988) A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa. Westview Press.

[9] Lewis, I. M. (1989) The Ogaden and the Fragility of Somali Segmentary Nationalism, African Affairs, Vol. 88, No. 353: 573-579.

[10] Lewis, I. M. (1988), op. cit.

[11] Drysdale, John (1991) A Review of Somalia: A Nation in Turmoil. Journal of Anglo-Somali Society, Autumn 1991, pp. 9-10.

[12] Harrison, Paul (1981) Inside the Third World: The Anatomy of Poverty. Penguin Books, p. 367.

[13] Lewis, I. M. (1991) ‘The Recent Political History of Somalia,’ in Barcik, K. and Normak, S. (eds.) Somalia: A Historical, Cultural, and Political Analysis. Uppsala, Sweden: Life and Peace Institute, pp. 5-15.

[14] Ibid., p. 14

[15] See Siyad Barre at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siad_Barre

[16] See ‘Obituary: Mohamed Siad Barre’, by Richard Greenfield, op. cit.

Leave a Reply