By Markus Virgil Hoehne

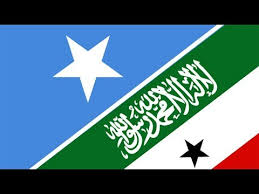

Recently, on 14 October 2024, Sagal Mohamed Ashour published a think-piece in HornDiplomat . In it she addresses the negative effects of what she calls the “clan system” on politics in the Somali territories. In particular, she focuses on the upcoming elections in Somaliland, the crisis over Lasanod and challenges in southern Somalia regarding the fight against Al Shabaab. In this reply, I will, based on long-term research on Somali issues and extended periods of field research in the north, argue why “clan” should not be demonized.

In my view, patrilineal descent is only one (albeit an important) aspect of a much more extensive kinship system, which is relational, effective, flexible and mobile, and within which Somalis organise central aspects of their everyday lives. This kinship system is a cultural asset of Somalis (actually one could call it “immaterial cultural heritage”) that should be preserved. It is a true alternative to (the originally European) concept of “nation state”, which in many regards is exclusionary, inflexible and, if undermined by parochial (e.g. tribalistic) interests, can be very harmful. In the following, I will outline my points in reply to passages of Sagal’s text.

Sagal writes “Clan systems are regressive and do not serve any purpose in a world driven by ideologies, values, socioeconomic position, and faith.” I would agree in the sense that “clan systems” are opportunistic. In the name of clan, people do not strive for an abstract “aim” or ideology like “free market” or “class-less society”. In the name of clan, people strife for the concrete well-being of their patrilineal descent group (first) and those with whom they live in everyday contact – often in-laws from other patrilineal descent groups/clans – (second). The latter is often overlooked. In everyday life, clan does not equal clannism/qabyalaad, which refers to manipulating patrilineal descent groups to maximize personal gains. The latter is what warlords or politicians like to do. In everyday life, clan (qabiil) only functions in relation to others, to whom one is related as neighbours, through intermarriage, or through the clan of the mother (whose relatives then become abti ama ina abti). This means, in everyday life, clan is not exclusive but inclusive respectively connected. Elders – at least the ones really working for their people and trusted by them – know that the overall aim always must be to live in harmony together with the neighbours, so that people and animals can prosper. In the semi-arid environment of northern and central Somalia, resources are frequently scarce and a way of sharing is necessary to secure the survival for all. Thus, qabyalaad or clannism functions anyway better in cities, where people do not depend on wells of neighbours, and where resources often come from outside (through aid, international private investments etc.).

Against this backdrop I disagree with Sagal’s point that “Clan systems are regressive and do not serve any purpose”. They are very progressive in securing the well-being of patrilineal descent groups and their neighbours in the hinterlands of the Somali peninsula. They are very effective since they are based on consensus, meaning: if the elders come to a conclusion, the whole group can support it. Women are formally excluded from decision making, but have a say in the background. Women also can mobilise elders to take decisions in case of need. Somali folktales are full of vocal women agitating their men or finding ways of getting things done. Still, there is a patriarchal element in the clan system (reinforced by Islam). Yet, within it, women are also protected. Somali women in the countryside can walk alone with animals, even with gold worth thousands of US dollars on their arms, and usually they are not harmed, because any thief would know that if he harms her, he likely will be hunted down by her relatives. So, clan systems can offer protection and secure survival. Yet, they are opportunistic in the sense that they only engage with most urgent issues (and ad hoc). They are limited in the sense that it would be hard to advocate for “ideological aims” like, e.g., ecological issues or equal rights for women or minorities within the system – unless these aims could be harmonised with existing normative orientations based on Islam (which is the case, in some regards).

Sagal continues: “Somaliland is good enough for you and me as an identity, after which you can discuss your city, town, or village all day long. However, if being a Somalilander is not enough for you and me, then nationhood will pay the price.” It is somewhat dishonest not to acknowledge that Somaliland as it was established in 1991 was based on clan, not on nationality. It was clearly driven by the political will of Isaaq, who are the demographic majority in the northwest. Others (Gadabursi and Ise in the far west and Dhulbahante and Warsangeli in the east, plus minorities like Gabooye or Gahayle) were not so enthusiastic to declare Somaliland’s independence at the meeting in Burco in May 1991. This has been discussed countless times and there is no need to repeat the details. What is more, however, is that during the formation process of Somaliland as de facto state through the 1990s and early 2000s, more and more an Isaaq narrative was taken as the narrative of the state of Somaliland. The memorials in Hargeysa celebrate the SNM, the struggle against Barre, and British colonialism. Yet, for many non-Isaaq, these are controversial issues (as is well known). Finally, in the course of the democratisation with multi-party elections since 2002, with each election the power of Isaaq in the government increased. Those in the peripheries, with the exception of Gadabursi, dropped out over the years.

Today, the vast majority of all MPs in the lower house is Isaaq, and all really powerful positions in the government and security apparatus of Somaliland are staffed with Isaaq. To say that “Somaliland is good enough for you and me as an identity” is just veiling the clannism (in the sense of qabyalaad) on which Somaliland is built – and the clannism is worse today than it was in the 1990s (when consensus between different clans provided the basis for peace making). Unluckily, Somaliland is not a nation today, and this can be seen from the current electoral campaign – in which the decisive question is which of the major Isaaq clans will vote for which party. This form of clannism is openly propagated by the political leadership of Somaliland. So, it is not the elders who are clannish, but Muse Bihi, Mohamed Kahin and many others in leading position in the Somaliland government. They try to manipulate clans to secure their personal power. This is the text book definition of qabyalaad.

Sagal asks: “When will we realize that the concept of clans belongs in museums?” In my view, the clan system should not go to the museum. It is a cultural asset Somalis (and other similar societies) have developed. It is much more than just “qabiil”. It is tol, it is xidid, it is abtiyaasha, it is relationship through kinship on all sides and agreements forged through xeer. Somalis (cognitively) master a kinship-based universe of social relations that Europeans or North Americans could not even think about, let alone use effectively. The beauty of this system is: it is not localized. Nations etc. are territorialized. They are bounded. They provide services to citizens, not to others. Passports are limiting who belongs and who not.

The Somali kinship-based order is deterritorial. It connects people in Burco, Mogadishu, Nairobi, Minneapolis, Helsinki, Berlin and Mumbai within seconds (thanks to telecommunication technology including internet-based ones). It connects villagers with urbanites and nomads with peasants. Within this mobile and flexible system, people belong in multiple ways – in the father’s line, on the mother’s side, through marriage, as neighbours etc. Somali migrants coming e.g. to Europe without any orientation find within minutes some relatives who can support them. Diaspora Somalis send remittances back home within seconds to support families and projects on the very local level. Somalis hold multiple passports and still feel they belong together. All of this works based on kinship and trust within extended kinship networks (also beyond “clan” in the narrow sense). A territorial national order, in contrast, is much more exclusive and inflexible than the “clan system” (better: kinship system) of Somalis. Nation builds borders, kinship builds connections.

Regarding the Lasanod conflict, Sagal writes: “It was driven by clan and tribalism. LasAnod had elected representatives through the democratic processes of Somaliland, yet tribalism ignited, fueled, and exacerbated the conflict.” The genesis of this conflict is complex. It was certainly not ignited by tribalism/clannism alone, and certainly is not a recent issue. It goes back to the very foundation of Somaliland – in haste – in 1991, in a time when many were traumatized by the civil war and people were standing on different sides. Isaaq as the majority pushed all others in the north in the direction of secession. Yet, most non-Isaaq (and even some Isaaq), especially in the east, never really accepted this. This did not mean that the others hated Isaaq (as some elites in Hargeysa try to make people believe). Indeed, when I was in Buuhoodle in 2004, the much respected elder Maxamuud Xaaji Cumar Camey summarized the situation as follows:

Maxamuud Xaaji Cumar Camey: You cannot separate Somalis. I am telling you the reason. They have the same religion, the same language, the same [skin] colour. We are a small people, only seven or eight million [people] of the same religion, language, skin [colour]. We are not going to separate, that’s for sure. [In] our land [here in and around Buuhoodle] we are brothers (walaalo) with those, and neighbours (deris) with the others.

Markus: Majeerteen are brothers (walaalo)?

Maxamuud: Yes, brothers.

Markus: Isaaq are neighbours (deris)?

Maxamuud: Yes, with them we are neighbours. Toward one side [Isaaq], language, neighbourhood, and nationality relate us. We are giving birth to each other [as result of intermarriage]; toward the other side [Majeerteen/Puntland], what relates us is [belonging together as] Harti and Darood. (Interview with Maxamuud Xaaji Cumar Camey, Buuhoodle, 12.03.2004).

This was twenty years ago, long before the recent crisis over Lasanod. This, however, was ignored by elites in Hargeysa who established their Somaliland on the narrative that was accommodating, to over 90 percent, the sentiments of Isaaq, not all others in the north. Further factors contributed to the escalation of the Lasanod conflict in 2023, and I and others have written about them in more detail (see Crisis in Lasanod: Border Disputes, Escalating Insecurity and the Future of Somaliland and also Conflict in Las Anod and Crisis in Somaliland: External Investment, Intensifying Internal Competition, and the Struggle for Narrative ). Yet, in a nutshell, the conflict over Lasanod in 2023 has its roots in what happened 1991 and afterwards. Besides, the tribalism which happened indeed (especially on social media) was not only an issue of Dhulbahante elders and their followers, but also of the leaders of Somaliland in Hargeysa, as illustrated clearly in the speeches and actions of Muse Bihi, Mohamed Kahin, Edna Aden and many others, including their supporters on social media in 2023.

Finally, Sagal states: “Clan-based thinking cannot coexist with democracy in the long term.” This seems correct, at least if one thinks of democracy defined by a multi-party system and one-person-one-vote elections. Clan-based or better, kinship-based thinking is focussed on collectives. The individual is always embedded in larger family networks (which does not mean that the individual does not have agency; yet, agency is normally strongly grounded in “family interests”). The European tradition of democracy is focussed on individuals constructed as independent even of their nuclear families. Regarding Somalia and Somaliland (even they had different political trajectories over the past 30 years, they are still culturally similar), the question is, in my view, if a multi-party system and one-person-one-vote elections make sense, or if this only adds more conflict potential to an already fragile setting.

According to my experience, most Somalis in the Horn of Africa rely mainly on kin relations to arrange security and get their lives done. This is obvious in the countryside across the Somali territories. Even in cities like Hargeysa, people frequently live in neighbourhoods inhabited preferentially by patrilineal relatives and in cases of everyday conflict (if e.g. a mobile phone gets stolen or someone gets hurt in a football game or car accident), elders settle the issues (sometimes in cooperation with the police, which, however, rather assists the elders). Besides, across the Somali territories, diaspora remittances channelled through kinship networks contribute billions every year to local development. This means: what Sagal calls the “clan system” (what I would call kinship networks), which she criticises as serving “no purpose” in her essay, actually supports Somali lives big time. The current quarrels in Somaliland over elections and also regarding the Lasanod crisis show that a state system that seems to be democratic and national (meaning: for all citizens), but actually has strong “tribalistic” undercurrents, can be harmful.

Markus Virgil Hoehne

Email: markus.hoehne@uni-leipzig.de

———————–

Author’s Biography

Markus Virgil Hoehne has been working on Somali issues since 2001. He received his PhD in 2011 from the Martin-Luther University Halle-Wittenberg for a thesis on state and identity formation in northern Somalia. His most recent project focuses on forensic anthropology in cultural context, based on research in Somaliland and Peru. He published “Between Somaliland and Puntland: Marginalization, Militarization and Conflicting Political Visions” (Rift Valley Institute, 2015) and co-edited “Borders and Borderlands as Resources in the Horn of Africa” (James Currey, 2010), “The State and the Paradox of Customary Law in Africa” (Routledge, 2018) and “Dynamics of Identification and Conflict: Anthropological Encounters” (Berghahn, 2023).

Leave a Reply