By Abdullahi A. Nor

“I earnestly pray that he may become Somalia’s next president, to rescue the nation from fragmentation and steer it toward peace, unity, and progress.”

In an era when the world was still largely silent on the legal injustices rooted in colonial history, one Somali legal scholar laid the intellectual foundation that would eventually reshape international legal thinking on indigenous rights, self-determination, and the invalidity of colonial-era treaties.

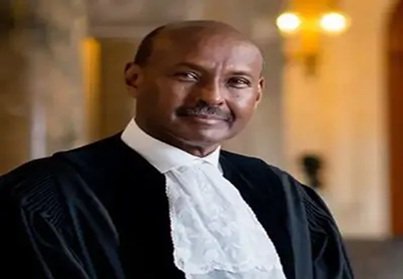

That scholar is Judge Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf, who until his recent retirement served as a judge at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the highest judicial body of the United Nations. Long before global institutions formally acknowledged indigenous rights, Abdulqawi’s 1980 legal research boldly argued that the forced transfer of Somali territories to Ethiopia under the 1897 Anglo-Abyssinian Treaty was illegal under international law.

His work offered not only a defense of Somali territorial integrity but also one of the earliest systematic legal critiques of the colonial order that has shaped, and continues to destabilize, the Horn of Africa.

The 1897 Anglo-Abyssinian Treaty: A Quiet Betrayal

To fully understand Judge Abdulqawi’s groundbreaking argument, one must revisit the context of the controversial treaty at the heart of his scholarship.

In 1897, the British Empire, seeking to stabilize its colonial holdings and suppress the Somali-led Darwiish resistance under Sayid Mohamed Abdulle Hassan, entered into an agreement with Emperor Menelik II of Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia). The British agreed to cede large swaths of Somali-inhabited territory in exchange for Abyssinian cooperation in preventing Somali uprisings in the region.

While the Somali clans had previously entered into “protection treaties” with Britain—agreements that promised the safeguarding of their autonomy and territories—these understandings were quickly discarded when the British negotiated directly with Abyssinia. Without consultation or consent from the Somali inhabitants, their lands were unilaterally handed over to Menelik’s expanding empire.

Under the terms of the agreement, Menelik was granted authority to govern and claim the Somali territories, while Somali pastoralists were permitted to graze their livestock seasonally across the newly imposed borders. This arrangement, however, masked the deeper violation of sovereignty that lay beneath—a violation that would haunt Somali-Ethiopian relations for more than a century.

Judge Abdulqawi’s Legal Intervention: A Bold Argument

In his 1980 article published in Horn of Africa, titled The Anglo-Abyssinian Treaty of 1897 and the Somali-Ethiopian Dispute, Abdulqawi challenged the legal validity of the treaty under international law. His central argument was both simple and profound: no treaty that transfers the land of a people without their free, prior, and informed consent can be considered legally binding.

He meticulously demonstrated how the British had not only breached their protectorate agreements with Somali clans but had also violated fundamental principles of state responsibility and sovereignty recognized in international legal doctrine. At the time of his writing, these principles had not yet gained widespread acceptance in international forums, making his scholarship even more visionary.

Importantly, Judge Abdulqawi also highlighted that the Anglo-Abyssinian Treaty remained in effect not only during the colonial era but continued to influence legal and political disputes even after the establishment of the League of Nations and the United Nations. The colonial legacy of artificial borders drawn without the consent of indigenous peoples continued to fuel tensions between Somalia and Ethiopia throughout the 20th century.

The Broader African Context: Echoes of Mamdani

Judge Abdulqawi’s work predated—but later paralleled—the critical analyses of scholars such as Mahmood Mamdani, whose 1992 book Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism became one of the most influential texts on African political systems.

Mamdani argued that colonial administrations deliberately created legal dualisms to maintain control: customary law was imposed on colonized subjects, while common law applied to settlers and colonial officials. This dual legal structure cemented divisions and inequalities that persist across African states to this day.

While Mamdani’s work focused on the internal mechanisms of colonial governance, Judge Abdulqawi’s research targeted the international dimensions of colonial injustice, particularly the unlawful transfer of territories and the denial of self-determination for colonized peoples. Together, both scholars exposed different facets of the same historical machine—an imperial order designed to benefit colonial powers at the expense of indigenous populations.

Somalia’s Modern Struggle for Sovereignty

More than forty years after Judge Abdulqawi first published his legal findings, his arguments resurfaced—this time echoed by Somalia’s own leadership in the face of new threats to its sovereignty.

In early 2024, Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud invoked many of the same legal principles outlined by Abdulqawi when he publicly rejected Ethiopia’s latest attempt to encroach upon Somali territory. The controversy arose after the Somaliland administration, led by Muse Bihi Abdi, signed a memorandum of understanding with Ethiopia, offering Ethiopia access to a naval base in the port of Lughaya in exchange for potential recognition of Somaliland’s self-declared independence.

President Hassan Sheikh firmly opposed the deal, asserting that Somalia could not tolerate any further dismemberment of its sovereign territory, particularly while historical grievances over Ethiopian-occupied Somali regions remained unresolved. In doing so, he implicitly drew upon Abdulqawi’s argument that colonial-era treaties lacking the consent of the indigenous population hold no legal standing under international law.

The 2024 crisis served as a stark reminder that the legal wounds inflicted over a century ago continue to fester in the Horn of Africa, destabilizing relations between neighboring states and undermining regional peace.

Ethiopia’s Ethnic Federalism: A Legacy of Menelik’s Empire

Judge Abdulqawi’s analysis also resonates within Ethiopia’s own internal political struggles. The expansion of Menelik II’s empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was not limited to Somali territories. Through military conquest and political coercion, Menelik incorporated vast regions inhabited by Oromos, Sidamas, Afars, and other non-Amhara populations.

These annexations laid the foundation for Ethiopia’s contemporary system of “ethnic federalism”—a fragile arrangement that attempts to balance ethnic self-governance with a centralized state structure. However, this system remains deeply contested, with many non-Amhara groups viewing it as a continuation of imperial domination rather than genuine autonomy.

The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which led Ethiopia for nearly three decades, has also challenged Ethiopia’s imperial history, portraying Menelik’s expansion as an era of oppression and forced assimilation. Monuments such as the Sayid Mohamed Abdulle Hassan statue in Jigjiga and the Anoole memorial in Oromia stand today as symbols of the atrocities committed during Menelik’s campaigns.

The legacy of forced annexations, cultural erasure, and political exclusion continues to fuel ethnic tensions and periodic violence throughout Ethiopia, underscoring the enduring relevance of the legal questions raised by Abdulqawi decades ago.

The Global Shift: From Margins to Mainstream

When Judge Abdulqawi first published his article in 1980, few international legal bodies were prepared to address the injustices of colonial-era border agreements. Yet over time, his once-radical argument has found its way into international legal doctrine.

The most significant milestone came in 2007, when the United Nations General Assembly adopted the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). This landmark document enshrined the very principles Abdulqawi had articulated: that indigenous peoples have the right to their lands, territories, and resources, and that any relocation or transfer must occur only with their free, prior, and informed consent.

While UNDRIP is not legally binding, it has become a powerful reference point in legal, diplomatic, and human rights debates around the world, offering indigenous communities new avenues to contest historical injustices.

A Lasting Legacy for Future Generations

Judge Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf’s contribution to international legal scholarship remains a remarkable testament to how one voice, grounded in rigorous legal analysis, can challenge entrenched historical narratives and offer alternative pathways to justice.

As global conversations increasingly grapple with the legacies of colonialism, land dispossession, and indigenous rights, Abdulqawi’s work stands as both a pioneering academic achievement and a moral guidepost. His scholarship not only defended Somali sovereignty but also provided a universal legal argument applicable to countless indigenous struggles worldwide.

In a world still navigating the unresolved consequences of empire, Abdulqawi’s work ensures that legal accountability for colonial transgressions remains an ongoing—and increasingly urgent—discussion.

Abdullahi A. Nor

Email: abdulahinor231@gmail.com

———

References

- Yusuf, A.A., 1980. The Anglo-Abyssinian Treaty of 1897 and the Somali-Ethiopian Dispute. Horn of Africa, an Independent Journal.

- Mamdani, M., 1992. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism.

Leave a Reply