By Bashir M. Sheikh Ali

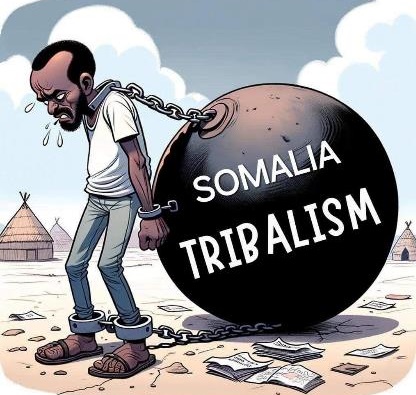

The story of Somalia cannot be told without reckoning with the enduring weight of the clan. For centuries, clans provided protection, identity, and rules for social life. They mediated disputes, secured alliances, and ensured survival in an environment where centralized authority was absent. Yet this very structure that once sustained Somalis now traps them in a cycle of mistrust and fragmentation.

To understand this paradox, it is useful to step outside Somalia and compare its experience with other societies that were once organized by clan and kinship, yet moved in different directions. From Greenland in the Viking age around the year 1000, to Ireland’s long struggle against English conquest in the late medieval and early modern periods, to Morocco’s shifting balance between tribal autonomy and monarchy through the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, to France’s decisive turn away from kinship-based order during and after the French Revolution of 1789, we can see how clan systems both nurtured and suffocated nationhood. These comparisons shed light on why Somalia still stands at a crossroads between the rule of the clan and the possibility of a united political community.

Greenland’s history illustrates how kinship can provide order in the absence of state structures, but also how fragile such systems are in the face of external pressures and internal divisions. Around 985 CE, Norse settlers established communities in Greenland, organized not by states or monarchs but by extended kin groups and assemblies. Like Somali clans, these kin groups bound people together through obligations of protection and vengeance. But by the fifteenth century, Greenland’s Norse settlements collapsed. Archaeological and written evidence suggests that as resources dwindled, kinship-based governance proved unable to adapt. Violence and feuding replaced cooperation, and without a state to enforce broader order, communities disintegrated. This history mirrors the Somali predicament in striking ways. Today, when the Somali state falters, clans cannot prevent violent groups from filling the vacuum. Al-Shabaab’s dominance in areas without government demonstrates that clan loyalty alone is insufficient to resist armed organizations. Just as Greenland’s kinship society dissolved when it could not protect its people, so too Somalia faces the danger that clanism, once a shield, has become brittle in the face of modern threats.

Ireland offers another revealing parallel. For centuries before English conquest, Irish society was organized through kinship networks known as clans or septs. Each clan had its own territory, leadership, and code of honor, much like Somali lineages. In the twelfth century, Norman invaders began the long process of colonization, but Irish clans resisted fiercely, relying on kinship solidarity to defend autonomy. Yet by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, English power grew irresistible. The Tudor conquest and later Cromwell’s campaigns in the mid-1600s crushed the old clan structures. What is crucial here is that Ireland’s fragmentation into clan and sept identities prevented the emergence of a unified national resistance until it was too late. English rulers exploited divisions, playing clans against one another. This echoes Somalia’s experience since independence in 1960, when the failure to build national institutions left Somalis vulnerable to internal strife and external manipulation. Just as English administrators used Irish clan rivalries to tighten their grip, Somali politicians and foreign powers exploit clan divisions to entrench their authority. Ireland eventually forged a national movement in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, culminating in independence in 1922. But that long delay shows the danger of relying on kinship identities when broader unity is needed.

Morocco’s experience underscores the uneasy balance between tribal autonomy and central monarchy. From the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, Morocco was divided between the Bled el-Makhzen—areas under the Sultan’s direct rule—and the Bled es-Siba, where tribes governed themselves by their own customs. In the Siba regions, much like Somalia’s stateless zones today, kinship structures provided order, but only up to a point. The Sultan often tolerated tribal independence, yet whenever central authority weakened, tribal groups could become centers of rebellion or lawlessness. Over time, Morocco managed to integrate tribal society into a modern nation, not by eliminating clans outright but by subsuming them under the authority of a centralized state. This process was uneven and sometimes through violence, but it prevented Morocco from descending into Somalia’s level of fragmentation. The Moroccan example highlights that while clans may coexist with state structures, they cannot substitute for them in the long run. Somalia’s tragedy lies in the absence of such integration. Unlike Morocco, Somalia has never had a sustained central power capable of subsuming clans into a functional political order. Instead, every attempt at centralization, from Siad Barre’s dictatorship in the 1970s to the fragile federal government today, has either collapsed or relied on the very clan divisions it sought to overcome.

France presents the sharpest contrast, and perhaps the greatest source of hope. Before 1789, much of rural France was governed by kinship ties and local seigneurial authority. Honor, family alliances, and customary law structured social life. But the French Revolution shattered this world. In its place, revolutionary leaders promoted the idea of the citizen as an individual, equal before the law, liberated from the bonds of lineage. The Napoleonic Code of 1804 further entrenched this vision, creating a modern legal order that subordinated kinship to the state. France’s transformation was not bloodless—the Revolution unleashed terror and civil war—but it decisively broke the hold of clan-like identities. What emerged was a nation bound not by kin but by shared citizenship. For Somalia, the French experience is instructive. It shows that moving beyond clan requires not just institutional design but a profound cultural shift: from loyalty to kin toward loyalty to a political community. Yet it also warns that the transition may be turbulent. Without leadership willing to guide the people through that turbulence, Somalia risks remaining trapped in the halfway state where clans dominate but the government is too weak to replace them.

Somalia today reveals the paradox of the clan in its most acute form. On the one hand, clan identity structures politics, mediates disputes, and provides solidarity. On the other hand, it blocks the emergence of national unity. Where the state is absent, clans cannot provide lasting protection. Al-Shabaab controls territory not because clans lack strength, but because their strength is fragmented and cannot generate collective authority — the collectiveness of nationhood is missing. The proliferation of arms across Somalia means that power flows to those with guns, not to those with respected genealogies. If clans arm themselves, they become indistinguishable from militias, perpetuating the cycle of violence. This is the paradox: the more clans are relied upon for protection, the less they remain what they were meant to be, and the more they become just another faction in a landscape of armed groups.

The lesson of history is sobering. Greenland’s clans collapsed into oblivion when they could no longer adapt. Ireland’s clans lost their independence and only after centuries of colonization did they give way to national consciousness. Morocco’s tribes endured but only by submitting to the authority of the monarchy. France broke free from kinship through revolutionary upheaval. Somalia stands at a point where these roads converge. It cannot return to a past where clans guaranteed order. That past is gone, buried by decades of war, the rise of violent movements, and the flood of modern weaponry. Nor can it survive by remaining in limbo, half clan-based and half state-based. The choice is stark: either Somalis come together to build a government that belongs to the people, or they will remain at the mercy of armed groups that seek to control them. Puntland and Somaliland demonstrate the power of even modest governance to provide stability. But they also show the limits of small polities in a world of geopolitical competition. A fragmented Somalia, even if peaceful in pockets, would be too weak to defend its sovereignty. Only a united Somalia can resist domination by external powers.

What France teaches is that change is possible, that societies long governed by kinship can be reborn as nations. But it also shows that the process requires courage, sacrifice, and leadership. Somalia must undergo a transformation in which clan is redefined—not as the foundation of politics but as a cultural identity compatible with citizenship. The script of endless violence, where those with guns always dominate, can only be rewritten by building a government strong enough to guarantee justice and security for all. This is not an easy task, but neither was it easy for Ireland to rise from centuries of colonization, or for Morocco to integrate rebellious tribes, or for France to leave behind centuries of feudal hierarchy. The past is not destiny. It is a warning and a guide.

Somalis today live in the shadow of this choice. If they cling to clan as the basis of order, they will find only disorder, as groups like al-Shabaab and others yet to emerge exploit the vacuum. If they rise above clan and create a government of the people, they can finally fulfill the promise of independence first proclaimed in 1960. The fate of Somali nationhood depends on whether Somalis can learn from history—that kinship may provide belonging, but only collective governance can provide freedom.

Bashir M. Sheikh Ali

Email: bsali@yahoo.com

———

The author is a Somali-American lawyer based in Nairobi. The views expressed in this op-ed are his own and do not reflect those of any organization with which he may be affiliated.

——-

Related articles:

Tribalism and its challenges to state formation in Somalia By Dayib Sh. Ahmed

Tribute to the mighty genius of Somali clannism By Prof Said S. Samatar

Leave a Reply