By Faisal A Roble

“According to the center–periphery model, underdevelopment is not the result of tradition, but is produced as part of the process necessary for the development of the center.” Immanuel Wallerstein

With its multi-ethnic population hovering around 105 million and inching towards 160 million by 2040, Ethiopia is a country with a unique history and geography. It is a country that serves as a source of pride for many Africanists, yet it is the only African country that supposedly colonized other African peoples. Until recently, some commentators compared it to Russia in the sense that both countries have been dubbed “prison of nations.” In the most extreme aspects of the Ethiopian history, people were enslaved just as much as Africans were enslaved by Europeans, argued Assafa Jalata. Such an equal social relationship between the colonized and the colonizer made state-building in Ethiopia challenging.

The question at hand is whether a distant and a decayed center that is showing its own internal cracks can hold disparate groups together within an undemocratic polity.

Several factors have challenged state-building in Ethiopia. Of these, two stand out; one is the question of nations and nationalities which is the result of the hegemonic political culture Abyssinians imposed on a decidedly defiant periphery region. The second factor is the ever-decaying center that could no longer hold together or exploit the peripheries some of which could be considered Ethiopia’s frontier, ala Somali region. The lethal combination of a freer periphery region and a progressively decaying center is more powerful than the sentimentality of the often-repeated pax-Ethiopiana that served as a source of pride for the centrists.

This essay will argue that state-building in Ethiopia has been shunned off by the center’s persistence hegemonic culture over a defiant periphery. If Addis Ababa fails to democratize the state, Ethiopia as we know it could cease to exist.

State Decay at the Center

In the past, centrifugal forces born out of lack of democratization of the Ethiopian polity and its inability to integrate those colonized into mainstream Ethiopia arguably encouraged periphery regions to constantly revolt. However, now that the center itself is decaying as did past empires elsewhere (The Ottoman, Austro-Hungary, Russia, as well as the former Yugoslavian federation), it is increasingly becoming difficult to hold the periphery with the center, or even hold the center itself together. In the last stage of an imperial life cycle, the cost to maintain Ethiopia’s expansive geography both militarily and administratively is prohibitively exorbitant. Paul Kennedy’s “The Rise and Fall of Great Powers: Economic Changes and Military powers” is instructively delineates the challenges empires often face and the tale-tell signs of imminent empire’s imminent decline. In short, maintaining a non-democratic empire is doomed to destruction.

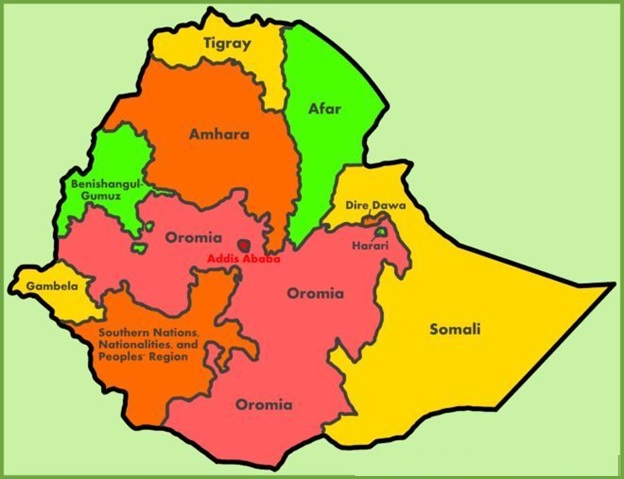

Three recent political developments have eroded the power the center had over the rest of the vast geography of Ethiopia. First, a rapidly growing urban middle class from ethnic nationalities have pressed for more democratic rights throughout the country. The mismanagement of Addis Ababa’s long-range master plan and the sprawl-oriented development of the City that expropriated the Oromo peasants is a matter of immense interest but beyond the scope of this essay. Second, the 1974 proclamation of land ownership, a revolutionary law that handed about 10 billion hectors of arable land back to smallholders who are mostly in the southern/eastern parts of the country (Ed Keller, 1988) weakened the center’s grip overpower. Last but not least, the passage of 1995 Ethiopian Federal Constitution which legally rearranged power by designating about 9 autonomous regional power geographies (Ethiopian Federal Democratic Constitution 1995) has sealed a major portion of rights demanded by ethnic groups. Therefore, deciding the fate of Ethiopia is no longer the exclusive domain of the center, but a matter equally to be negotiated and decided with the periphery regions. Whether the new center of power located in the Oromia can be a unifying linkage between the center and the periphery in a fully democratized Ethiopia is yet a thing in the future.

The center has shown major internal cracks and has lost its absolute power. The pillars that hitherto united the center, including but not limited to, the Orthodox Church, the aristocracy, tightly knit bureaucracy drew from Amhara-Tigray coalition, and foreign military and diplomatic alliances have either dried up or are significantly weakened (Ed Keller, 1988). For Example, the proliferation of the Pentecostal Church that is siphoning congregation members from the Orthodox Church, rapid urbanization in highland Ethiopia, a dwindling surplus from the south, and institutionalization of regional governments in the last thirty years have collectively contributed to the making of deep and possibly irreparable cracks in the center (Faisal Roble, 2018). The Amhara-Tigray alliance is for the time being dead, and the past commitment to impose hegemony on the non-Abyssinian south has run out of steam thereby making state-building in its imperial form more challenging. In Highland Ethiopia, signs of rebellion against the state – a phenomenon in the past associated with the periphery is tearing the traditional Amhara-Tigre Faustian pact.

In the last few years, much interest has been given to the study of decaying states. In his recent book, “The Horn of Africa: State Formation and Decay,” Christopher Clapham, a known Ethiopianist, although attempts to deal with this subject, comes short of living up to the title of the book. Written in 2017, he dwells on Somalia’s experience when discussing state decay, but completely ignores the consequential decay of the Ethiopian center. At the time of the publication of the book, Highland Ethiopia was ablaze with ethnic conflict. In an untimely sentimental way, Clapham’s discussion retreats to the familiar terrain of a “glorious” Abyssinia. As an avowed student of Abyssinian history and an author of several books on Emperor Haile Selassie, Clapham maintains that Ethiopia has “historically created the power structures to which the peoples of the peripheries have been, and to a large extent continue to be, subordinated.” Perhaps that would have made sense several decades ago. In today’s Ethiopia, however, the center shows many fissures, and the power that traditionally resided in Abyssinia has moved to the middle of the country and sits in the hands of Oromo.

Calpham makes another fallacious assertion in that the “pastoralist zone” is the zone where “conflict is inherent.” Perhaps so in the past when Somalis, Borana Oromo, Sidama, and Afar had to wage wars for liberations. Today, the reality on the ground undermines this argument, as more conflicts and armed militia have clouded Highland Ethiopia. Driven by both old and new identity politics, thousands of heavily armed militias are facing each other on the shared borders between these two regions. On the regional border of Eritrea and Tigray and Tigray and Amhara regions, their respective tripartite troops are dug in with the potential to exact heavy casualties on each other if the current low-intensity conflict escalates. Add to this the blue-helmeted UN peacekeepers along the Tigray and Eritrean border, and you have a highly militarized, if not one of the most militarized zones, in Africa. On the contrary, lowland zones are comparatively more peaceful. As a matter of fact, northern Ethiopia is today divided militarily, politically and socially, all of which typify the attributes of the decaying Abyssinian center.

None other than the recent foiled coup of June 23, 2019, engineered by the extremist Amhara nationalist, General Asamenew Tsagia, indicates the crescendo of the decaying of the center. The Crisis Group wrote “the 22 June assassinations and alleged the attempted regional coup came as a stark illustration of the gravity of the crisis affecting both the ruling party and country.”

Victims of the coup included Amhara’s state president, Ambachew Mekonnen — who is an ally of the prime minister — and Mr. Ambachew’s adviser, Gize Abera, were also killed in the region, according to state media. In Addis Ababa, the chief of staff of the Ethiopian Army who was a Tigray by ethnicity and at least three other senior officials were killed. The rebel group wanted to turn the clock back to the political culture of Imperial Ethiopia.

Different experts and scholars looked at the implications of the foiled coup through different prisms. Herman Cohen, former Undersecretary for African Affairs commented in a tweet dated June 24, 2019, that the coup was “an attempt by Amhara nationalists to restore Amhara hegemony…” Only days before the coup, Jonnie Carson of the United States Institute for Peace (USIP) warned of the potential disintegration of Ethiopia. In a high-level conference dubbed “A Changing Ethiopia: Lessons from the US Diplomatic Engagement,” the last serving four US ambassadors assigned to that country (1991 through 2006) shared their instructive insights about the decaying polity of that country. The diplomates all agreed on the stubborn culture of Abyssinian, an attribute that could lead to the country’s disintegration.

Jonnie Carson, who in the past served as the United States Undersecretary for Africa Affairs during President Obama’s administration and a long-time career diplomat delivered impacting introductory remarks assessing the changes that are taking place in Ethiopia. Without mincing his words, Ambassador Carson loudly expressed his fears of a potential disintegration of Ethiopia and likened such a possibility to the former Yugoslavian experience. Prior to this type of USIP meeting, the leaders of the institute are often privy of valuable diplomatic and security information. It is, therefore, more than a mere coincidence, and therefore, unthinkable to delink Ambassador Carson’s weighty remarks from the foiled coup of June 22. For Carson to openly raise stakes so high in public and pronounce the possible disintegration of Ethiopia was but a serious matter. And it so remains.

Ethiopia is certainly fragile. As the global leader of internally displaced persons since World War II with 3.5 million people losing their homes and livelihood, political upheavals have wracked the country. This time, most of the conflicts are in the center and less in the peripheries. If John Markakis and others cataloged the historiography of this dying ancient empire threatened by the periphery, disintegrating Ethiopia is the work of a decaying core region.

The last gasp of ruling the periphery is through a new and non-traditional center whose authority leans more on regional states run by local elites at the helm of the regional state. An in-depth look at the history of the Somali region shows that Haile Selassie and Mengistu Haile Mariam ruled their region in the same manner that Lord Lugard ruled Britain’s colonies in Africa – that is working through a proxy elite group, including traditional elders, while governance and real power was in the hands of a vast military and security apparatus recruited from and loyal to the center. However, beginning with the creation of nominal autonomous regional states in 1991, which is currently the units of administration both in the center and in the periphery regions, ethnic groups in the peripheries are ruled through what the French colonial power called evolve’ (evolue’).

With evolve’, the Abyssinian hegemonic system created a class of indigenous miscegenated or assimilated individuals whose loyalty and theoretical constructs are in line with the ruling elite in the center. Unlike the case with the French-style evolve’, which was mostly educated, Ethiopia’s once-dominant party system created a pseudo-socialist but less educated “cadre” that carries out the orders of the center. It is precisely because of their subservient positions that most of the regional cadres failed to meaningfully empower their citizens.

In a recent critical study about Oromo elite inclusion into the ruling clique of Abyssinia (Regime Change and Ethno-Regionalism in Ethiopia: the case of the Oromo, 1998), Ed Keller is perplexed at the small number of Oromo elite that had successfully joined or admitted to join the upper echelon of the ruling Highlanders. A recent survey conducted by the Oromo Media Network (OMN) found out that the number of Oromo professionals in major sectors of the economy is negligent. In the case of Somali elites, they are “behind by at least a century” to catch up with the center, writes Markakis. Somalis are entirely absent from the ruling echelon of Ethiopia no matter who ascends the seat at the Liyu Baliyu Palace.

Somali region is a not-yet fully conquered frontier, and as such one of the scenarios scholars stipulated to happen in the Somali region is for the center let go the Somali region for the posterity and future stability for the region. I will come back to this issue and its political implications in the last section of the paper. However, this observation – letting Somalis out of bondage – makes sense at a time when the very Ethiopian polity has decayed and the center itself is disintegrating. This argument is supported by the expansive study of Paul Kennedy (“The Rise and Fall of Great Empires: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000”), and his assessment of the life cycle of empires which is marked by ups and downs, ending with a debilitating decay and a final big bung leading to the death of the center, as it happened in the former Soviet Union. An Empire falls when it can no longer control, extract surplus, administer, or support its peripheral territories. In other words, its tired tentacles and dwindling resources limit its ability to control territories far removed from the center. It is within this context a new toolbox is needed to forge a democratic state-building project, including but not limited to free some of the periphery regions.

Wrong Tools, Rough Results

The Ethiopian state has traditionally consisted of two loosely organized entities: a geographically compact and culturally unified core region – also known as the Abyssinia Highland, and a vast disparate colonial geography in the periphery including but not limited to Somali, Afar, Sidama, Oromo, and other regions. Most of these nationalities in the periphery have not been fully integrated into the Abyssinia core region. For examples, almost entirely the Somali populous does not speak Amharic with almost any inter-marriage with Highland Ethiopians. Markakis believes that it will take at least a century for some of these periphery regions to fully catch up with the center. Somalis are one of the most frontier and difficult-to-reach regions with no real catch up chances or integration in the offing.

Therefore, there must be a paradigm shift that puts on the table state-building that only entertained in the past the traditional conservative notion of “preserving” the original imperial geography assembled at the turn of the 19th century. “Ethiopia’s leaders face a genuine dilemma, a choice between two risky alternatives. One is to make a clean break with the past, renounce center hegemony and accept equitable power-sharing with the periphery,” writes Markakis. Moreover, or else letting some periphery nationalities such as Somalis to secede (John Markakis, 2011, Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers, 2011).

In the final analysis, reforming state-building should not be an either-or proposition, but a combination of multiple approaches. Prime Minister Abiy’s democratization effort must not be limited only to the preservation of the center’s hegemonic grip over the periphery. Full-Blown democratization and a new paradigm to inject new tools to state-building – full democratization of the polity – must be designed. Prior regimes have used wrong approaches to solve the nationality question but to no avail. Previous administrations utilized ineffective tools to tame the country’s vexing political question – multinational question. During Haile Selassie, national laws entirely denied the existence of nationalities. Under the slogan of “agar ya gara, haymanot ye gili,” or, “the country is one, but religion is private,” while religious difference was recognized in an unequal manner, the question of nationalities was entirely denied. Ethnic groups were ruled through layers of feudal quasi-judicial authorities all of which catered to serve the land gentry class and oppress the rest. Moreover, ethnic regions were gerrymandered to minimize their political influence. For example, Somalis were divided into three provinces (Sidama, Bale, and Harar), where they were rendered minorities in all three provinces. The same was true for Oromo, Afar, and others.

Prior to this ethnic-based regional states, the country was administratively subdivided into 14 regions. The old map served well for surplus extraction by the center and accordingly perpetuate severe underdevelopment in the periphery regions; it also promoted gerrymandering of ethnic groups thus minimizing their political role in this ancient empire. For example, Somalis were spread out in three administrative geographies, namely Hararge, Bale, and Sidamo. And they played no mentionable role in any of these administrative regions. The same was true for other similar ethnic groups.

The Dergi also paid lip-service to the issue of nationality rights and gave some limited recognition to some of the periphery groups, especially to those distant and difficult-to-rule regions. Accordingly, Somali, Afar, and Eritrea (pre-1994) were given a limited, only on-paper recognition in the form of regional autonomy dubbed “Raz Gas”. So did the Dergi regime create Eritrea, Ogaden, Gurgura and Issa, and Afar Ras Gaz (regional autonomy for these three groups). Like its predecessor, the Dergi gerrymandered Oromo, Somali, Afar and other colonized groups. The Dergi’s goal was not to create autonomous regions but to further divide and rule periphery groups as well as contain the patriotic insurgency than relinquishing real rights to these groups.

On the other hand, Ethiopia’s federal system, adopted in 1995, sought to grant limited autonomy and mandated the creation of nine regional states, and two autonomous city-states (Addis Ababa and Dridhabe) with the goal to quell ethnic political strife. Despite the country’s lofty constitution, the grip of power by the center and hegemony over the periphery remains unabated. The lasting effect the new map and the constitution had, which calls nominally for the rights of nationalities to full statehood, is to programmatically reduce the grip on state power by any group. However, between 1991 and 2018, that total grip on power resided in the hands of the Tigray minority group. Whether Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s transition to a democratic system of government materializes is up in the air. So far, although Abiy the persona has liberal tendencies, the administration he presides over under the auspices of EPRDF is far from being democratic. It is a one-dominant party rule that cannot be called a democratic institution.

There are currently three competing forces that shape Ethiopian political narrative. The first group calls for a centralist government that seeks to remove Article 39 (the right of nationalities for self-determination) from the constitution (the party whose coup was foiled on June 22, 2019, Ganbot 7, and the National Movement of Amhara are on the forefront for this cause). This pack believes that multi-nationalism leads to disintegration. However, there is no proof to support this assertion and whether multi-national federalism causes disintegration.

The second group seeks to maintain the status quo per 1995 constitution, where autonomy for regions is only nominal and power remains in the center. Such has been the scenario in the last 27 years of EPRDF rule. Whether the transition to full democracy under the auspices of PM Abiy Ahmed materializes remains only a promise thus far. The third group comes from hitherto colonized peoples like Somalis, Oromos, Afars, and Sidama, whose right to self-determination is sacrosanct.

Navigating and/or mediating these narratives is the challenge PM Abiy faces. The push and pull factors associated with these groups form the source for the looming Ethiopian disintegration. Failing to mediate and equally accommodate these competing narratives could put Ethiopia on a course of total disintegration. I postulate that the following three scenarios are in store for Ethiopia if genuine democratization is not brought to bear on the ancient imperial polity.

Balkan or Yugoslavian Scenario: Some scholars, policy analysts, and diplomats are fearful of a potential “Balkan scenario” that could grip Ethiopia and destroy the country as we know it. Called by some the “Yugoslavian” scenario, a full-blown ethnic disarray with multi-dimensional conflicts will lead to a neighbor against a neighbor-type war and full-blown inter-ethnic mayhem of a large scale could be the result of this zero-sum game scenario.

For example, an Oromo-Amhara axis, a Tigrian-Amahara conflict zone, Afar vs Somali, Somali vs Oromo, as well as many more mini conflicts within the Southern states would be devastating. Several journalists who visited the region have blown the whistle for an early warning as the possibility of this scenario gathers momentum. A major ingredient of the factors that are precipitating the dawning of the Yugoslavian scenario is the EPRDF-sponsored 2004 redistricting of the region, which farther divided organic communities of the same ethnic group and instead forcefully placed them in cultures that they do not belong to. Moreover, the political decay and the heightened identity politics in Highland Ethiopia is parallel to what had transpired among major groups in Yugoslavia prior to the disintegration. Ethnic hooligans already dictating the political discourse is symptomatic or a precursor to the Yugoslavian debacle. Revisiting the redistricting of 2004, which rewarded some members of the EPRDF coalition, plus reclaiming the political space from extremists could help reverse the looming “Yugoslavian” scenario that many scholars and diplomats warned of. This is the most devastating and the least desirable scenario.

Russian Scenario: Dubbed the “Russian model,” this scenario stipulates a more managed divorce mainly of some periphery regions from the core regions of Ethiopia. Thanks to an insight I gained from a Swedish diplomat I met in Djibouti in December 2018, this scenario calls for traditional Abyssinians or Highlanders, consisting of Amhara and Tigray pack, would stay together following a serious mediation between them. These two groups share a common history and the Orthodox Church., which is losing membership fast. They also collaborated in the colonization project of the lowlanders. However, with recent crack, both politically and socially, attaining the Russian model is showing fewer promises.

Had the two Abyssinians remained in good terms with each other, this scenario would have been attractive in that it would have banded traditional Highlanders together. With a clean break up of the empire along north-south axis, the infrastructures, for example, the “Qoqa” electric grid system, interstate roads, Ethiopian Airlines Corporation, Telecommunication and other major investments that tie the center to the periphery, could be negotiated at the marketplace. If a breakup along this axis happens, the shared infrastructures, because all Ethiopians have invested for over a hundred years, would serve as the linkage between the ancient imperial core region and the newly formed countries such as Somali, Oromia, and Afar states. Many Oromo leaders as well as some Somalis often enthusiastically flirt with this scenario under the rubric of a newly found “Cushitic” brotherhood identity,” that may create a competing block in the periphery.

Self-Determination Scenario: In this scenario, Ethiopia would accept a negotiated settlement and move forward to authorize the full independence of primarily Somalis through legal means. This could happen through the implementation of Article 39 of the constitution, which guarantees nationalities the right to freedom through an agreed referendum.

The roots of Article 39 go back to the days of the Ethiopian progressive movements in the 1970s. Rooted in noble principles borrowed from both Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points on self-determination and Lenin’s treatise of “Critical Remarks on National Question,” the Somali-favored scenario is within the bounds of the international norm. Somali resistance has always been congruent with the principles of self-determination as promulgated in the United Nations Charter after World War II, which unequivocally upholds the right of nationalities. Under this international instrument, Somalis should decide their fate of social, economic and political wellbeing. Article I of the Charter of the United Nations embodies the concept of “The principle of self-determination” on “Civil, Political Rights Economic, Social and Cultural Rights” of oppressed peoples.

Herman Cohen, former Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs (1989-19993), believes that Western nations erred in placing the Somali Ogaden Region under Ethiopian rule; he even goes as far to argue that the Somali Ogaden question deserves self-determination more than South Sudan or even Eritrea.

Many empires and countries implemented the principles of self-determination. For example, before the Russian revolution of 1917, most Poland and Finland were under the Russian empire. Today, they are free and independent nations. Likewise, under Western pressure, Sudan was forced to grant South Sudan full independence. Even Ethiopia in the past has done so in that it permitted Eritrea to go free through a fair and internationally supervised referendum in 1994 (The Somalis have less affinity and no meaningful integration with Abyssinia than Eritrea). Common to all these experiences of self-determination was that they were either colonized or forcefully annexed by a predatory imperial or feudal states.

According to the Ethiopian constitution Somalia’s self-determination is a question of only when. As provided in provisions under Article 39, the Somali nation has the right to invoke this article any time the region is ready and would fulfill procedural requirements to effectuate the creation of an independent Somalia state outside the ancient Ethiopian empire. These surmountable procedural requirements memorialized in section 4 of the same article are as follows:

“When a demand for secession has been approved by a two-thirds majority of the members of the Legislative Council of the Nation, Nationality or People concerned; b. When the Federal Government has organized a referendum, which must take place within three years from the time it received the concerned council’s decision for secession; c. When the demand for secession is supported by a majority vote in the referendum; d. When the Federal Government will have transferred its powers to the Council of the Nation, Nationality or People who has voted to secede.”

If the Somali region is granted self-determination, this outcome may bode well for Ethiopia in the long run in that the newly “created Somali State” may serve as a linkage for the integration of Ethiopia-Djibouti-Somalia. In the belly of these states sits the Somali Ogaden region. In the final analysis, the decaying center and the surging ethnic strife forces us to think out of the box, even if that means remapping Ethiopia in the interest of stability and peaceful coexistence of the peoples of the Horn of Africa Region.

Concluding Remarks

Oromo leadership has Ethiopia’s Certificate of Remapping (COR), or as some skeptics would like to say, Certificate of Death (COD), in its hand. The prospect for a unified peaceful Ethiopia is predicated on a full democratized polity which so far is a pipedream. As it appears now, unity in Ethiopia may not be able to withstand the weight of painful history and the havoc that has been so far wreaked on oppressed peoples. Can it stand the weight of what a prominent but provocative American Social Scientist wrote that “a desire for recognition of one’s dignity is inherent in every human being―and is necessary for a thriving democracy”? Ethiopia must recognize the national desires of colonized nationalities and other groups either through an unbridled widening and democratized political space (full-blown federalism) or letting them exercise the option of independence and self-determination. Multi-national Federal Democracy is the only course that could possibly avert total disintegration of Ethiopia

As technology advances, urbanization takes roots, and democratic values make inroads into hitherto oppressed communities, holding people in colonial bondage is unsustainable. Implementing a full-fledged multi-national federalism rooted in democratic values is, however, possible and attainable option, if the leadership in Addis Ababa is prepared. Jonny Carson’s impacting remarks on June 5, 2019 at the United States Institute for Peace calling for democratization before disintegration should be read as a positive early warning system; If Addis Ababa fails to listen to the demands of its citizens, a “Yugoslavian” tsunami will wake it up!

Faisal A. Roble

Email: [email protected]

———–

Faisal Roble, a writer, political analyst and a former Editor-in-Chief of WardheerNews, is mainly interested in the Horn of Africa region. He is currently the Principal Planner for the City of Los Angeles in charge of Master Planning, Economic Development and Project Implementation Division

We welcome the submission of all articles for possible publication on WardheerNews.com. WardheerNews will only consider articles sent exclusively. Please email your article today . Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of WardheerNews.

WardheerNew’s tolerance platform is engaging with diversity of opinion, political ideology and self-expression. Tolerance is a necessary ingredient for creativity and civility.Tolerance fuels tenacity and audacity.

WardheerNews waxay tixgelin gaara siinaysaa maqaaladaha sida gaarka ah loogu soo diro ee aan lagu daabicin goobo kale. Maqaalkani wuxuu ka turjumayaa aragtida Qoraaga loomana fasiran karo tan WardheerNews.

Copyright © 2024 WardheerNews, All rights reserved